Academic medical centers (AMCs) are a triple threat on the healthcare court with their combined medical center, education, and research sections. With a unique set of resources, AMCs have the ability to take a comprehensive, holistic approach to patient care. However, one of the challenges they still face is utilizing healthcare analytics effectively within the patient care setting. With the Healthcare Analytics Adoption Model and other data expertise, AMCs can learn how to merge siloed data, while improving operations, and delivering the highest quality of care to each patient.

Download

Download

With its combined medical center, research, and education arms, the academic medical center (AMC) is a uniquely resource-rich member of the healthcare industry. However, despite this expansive access, AMCs still need more effective strategies to merge their disparate data and use that information to improve their complex mission—from delivering quality care and furthering medical research to educating tomorrow’s health care leaders.

We sat down with Dale Sanders, Health Catalyst Chief Technology Officer, to learn more about the role healthcare analytics plays in academic medicine, now and in the future, and how AMCs can better leverage these analytics as a strategic asset.

Four big things come to mind. First, is this paradoxical explosion of both genomic knowledge and genomic ignorance. The more we learn, the more we don’t understand. But we have to keep exploring and integrating genomic and clinical data spaces.

Second is the microbiome. If we think genomics and epigenetics are mysterious, the microbiome will make that mystery look like a nursery rhyme.

Third is the need to digitize the patient beyond the data we collect in a clinical or hospital encounter. We have to think more like electrical and aeronautical engineers who understand digital sampling theory, and aircraft and spacecraft health maintenance. This is the world of biointegrated sensors, like the work of John Rogers at Northwestern.

Fourth, I believe that the inherent needs of population health and the inherent cultural infrastructure of AMCs are a mismatch made in heaven, and that mismatch will end in divorce in the overwhelming majority of cases. Population health concepts are incredibly difficult to achieve in any case, as evidenced by the lack of measurable and sustainable success stories, but in AMCs it’s even harder. Everything about an AMC, from the ground up, is about novel research, and treatment of complex and unusual cases—not prevention and engagement with chronic disease patients that spans years, if not decades. I might even offer the provocative opinion that we, as patients and taxpayers, should discourage AMCs from engaging in population health so they can return focus to their core strengths, and leave population health to community hospitals and integrated delivery networks. Rare disease research, treatment, and prevention is a classic opportunity for AMCs to exert their fundamental strength, but population health is pushing aside rare and genetic diseases. I predict, with a pinch of hope, that AMCs will reduce their attempts to become experts in population health and revert back to their strengths or shift quickly to become an IDN like Partners and the University of Texas Health System. Either of those shifts will require a shift in healthcare data and analytic strategies.

The strategic options for AMCs to meet their future analytics and application development needs come down to the usual choices. They can build their own, which I don’t recommend. Those days are over. They can rely on their core EHR vendor because that’s the easy choice, and they’ve already spent a boatload of money on that vendor. The jury is still out as to whether the EHR vendors can turn themselves into data operating systems. It will take a major technical and cultural change for them to do that. And finally, AMCs can choose a data-first platform company like Health Catalyst. I honestly don’t know of another company like Health Catalyst that has the combination of healthcare-focused data technology with healthcare-focused domain expertise. One of the limiting factors to more companies existing in this space is the shear financial investment required to build the underlying technology, combined with the acquisition of knowledge of healthcare operations. It’s incredibly hard and unlikely to recreate what we’ve built at Health Catalyst.

Leaders in academic medicine are just beginning to recognize the effort to digitize the patient and the patient’s healthcare. It will be a 10- to 20- year journey to robust maturity and will never completely end. The technological platform that supports the digitization of the patient must be able to evolve gracefully over a similar period of time.

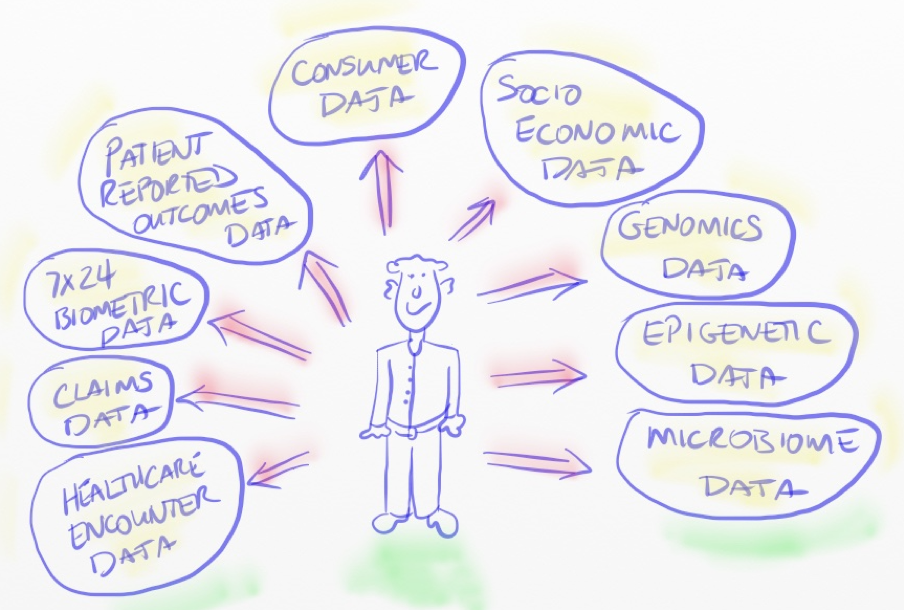

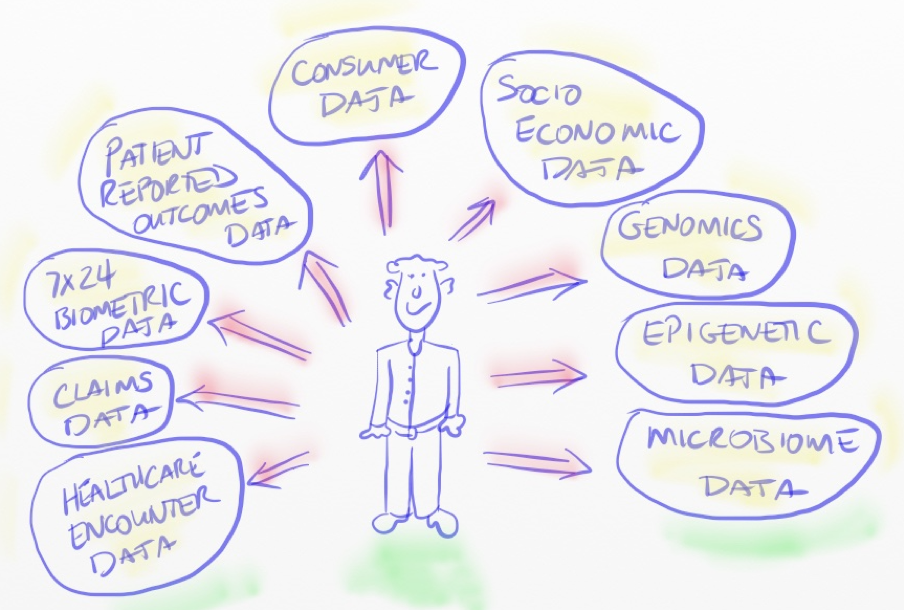

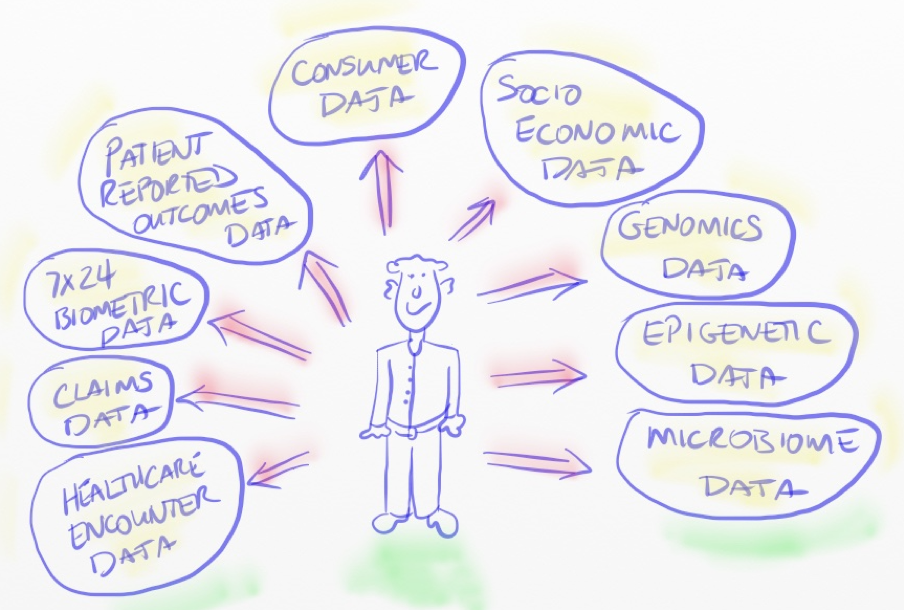

AMCs must develop a strategic data acquisition strategy that accounts for the roadmap and methods for collecting and leveraging the data depicted in Figure 1. I drew this cartoon in 2008, when I was at Northwestern, to represent the general categories of data necessary to fully understand the patient at the center.

For the most part, the data in the lower left quadrant of the drawing currently characterizes the realm of healthcare data and analytics. That’s where most of our data and analytics focus in healthcare currently resides. While that data content is certainly better than nothing, and can produce significant analytic value, it’s not enough to deliver personalized, precision medicine, one patient at a time. Population health is an inherently data-driven concept that begins one patient at a time, from the ground up, not from the top down.

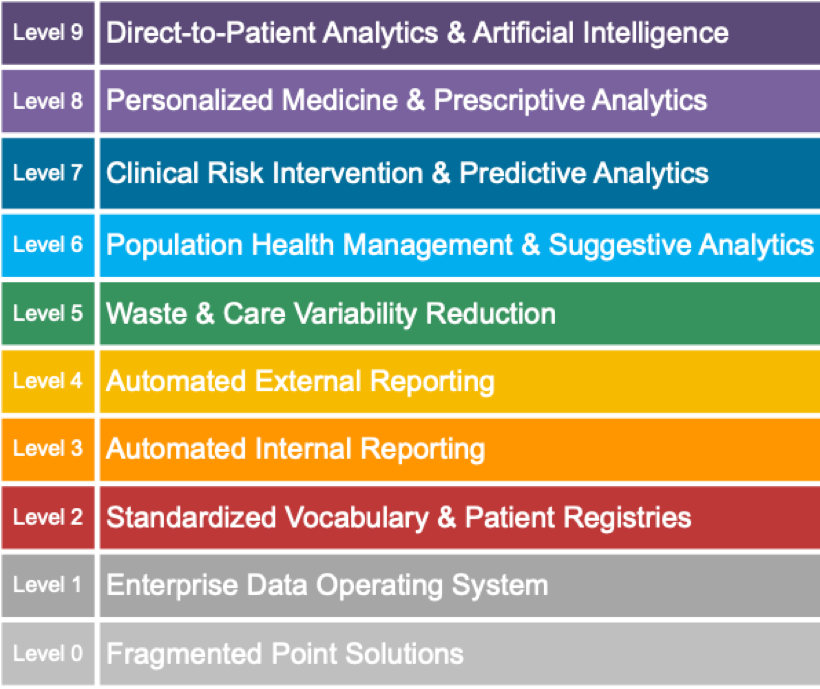

With invaluable help from many friends and colleagues, I co-published the Healthcare Analytics Adoption Model (Figure 2) in 2012 with Dr. Denis Protti of the University of Victoria-British Columbia. The model, and the details behind it, can be used to evaluate vendors, inform product roadmaps, and assess an organization’s state of analytic maturity. We granted its use to the Health Information Management Systems Society under creative commons copyright so that they could use it to conduct independent assessments, much like the service that they provide with the EMR Adoption Model.

The common problem we see in healthcare, especially in AMCs, is the tendency to pursue analytics at the upper levels while neglecting the lower levels of the model. Organizations often find themselves incapable of sustaining or scaling the analytics in those upper levels. By progressively working through each level of this model, AMCs can operate efficiently and sustainably at the upper levels.

At Level 1, your analytics model suggests the need for an Enterprise Data Operating System. Talk about that.

I call it the Data Operating System (DOS™) because the concept is more than a traditional data warehouse; the DOS concept supports analytics, application development, and record-level exchange of data, all from a single platform of consistent and reusable data.

Multiple, traditional data warehouses are common at AMCs. Typically, one of those data warehouses is centrally funded and managed to support healthcare operations, compulsory measures, and administrative management. Several other data warehouses typically exist and were born out of research grants. In addition to the costs associated with maintaining these redundant systems, their missions and data content become redundant, and even competitive, and create significant data governance problems. At Northwestern, we designed a single enterprise data warehouse to support all three missions of the AMC—education, research, and care delivery. We brought the lessons of that success story to influence at Health Catalyst and DOS. Gartner calls it a Hybrid Transaction/Analytical Processing architecture.

Right now, healthcare analytics and data are both the solution and the problem. Academic medicine suffers from the same problems of physician burnout, and maybe worse, that currently affect the rest of industry. There are a number of reasons behind burnout, but we believe the overwhelming demand on clinicians to support compulsory quality measures through data collection drives a significant portion. Many of these compulsory measures lack clinical relevance, so a physician’s clinical performance is ironically measured by the same irrelevant data points that burden clinicians. It’s a vicious cycle that strips away their sense of autonomy and mastery over their profession.

Because of the murky connection tying compulsory quality measures to clinical performance, Health Catalyst strongly advocates an analytics strategy that openly admits to the flaws in these compulsory measures while acknowledging the reality they currently play in economic reimbursement. Financially, they can’t be ignored. The strategy then, must reduce the burden for collecting this data and producing the related analytics through technology, while at the same time providing clinicians the data they want and need, when they need it, in the form they need it.

The public cloud makes big data technology—e.g., the Hadoop ecosystem, Spark, and NoSQL databases—particularly appealing to many AMCs. In my opinion and observation, the AMCs that jumped early into big data are not realizing the enterprise value and scalability they expected. Beyond the world of genomics, big data has had a small, and sometimes negative, ROI to healthcare analytics. Initially, the world of big data was portrayed as the replacement of traditional relational databases, but that has not been the case. Health Catalyst designed DOS keeping in mind that the worlds of big data and relational databases are now blending together into a hybrid architecture that leverages the best of both worlds.

It depends on how you define precision medicine, but if it’s delivering care protocols that are tailored to a patient’s genomic profile and understanding the phenotypic expression of disease based on clinical profiles, then yes, we’re talking about the same thing. Virtually all AMCs now engage in some form of precision medicine research. So far, however, precision medicine is not reaching patient care. In part, today’s EHRs make it very difficult, at best, to blend the synthesis of genomic and traditional clinical data together at the point of decision making. But, we can still work on the discovery of insights while we work on improving the delivery of insights. With DOS, or a similar platform, we can support the exploration of phenotyping in three different models:

The traditional approaches to natural language processing (NLP) in healthcare have not produced any widespread or sustainable value. I’ve watched it flounder for 25 years. So, like precision medicine, the value of NLP has not yet reached patient care, but we believe the next evolution of NLP will, as the focus of NLP shifts from attempts to extract discrete values from text, to a pattern recognition-based approach to analyzing clinical notes. We designed DOS as a platform that integrates discrete and text data in a single infrastructure, making the integration of discrete and text data a standard best practice.

As a platform that was designed specifically to support third-party application development, DOS enables vendors who specialize in NLP to plug their applications into the DOS infrastructure and leverage the DOS investment at client sites—rather than building, and clients paying for, another platform. Health Catalyst products leverage text data to support narrow domains of decision support and NLP use cases, such as those associated with our Patient Safety Monitor™ Suite: Surveillance Module.

Again, it sort of depends on how you define artificial intelligence (AI). My definition and views on AI go back to the early 1990s when I was working in the space, defense, and intelligence sector. At the fundamental level, AI is all about computerized pattern recognition and then responding or intervening according to the pattern. Sometimes the response is generated by the computer, sometimes the response to the pattern is generated by a human’s interpretation and brain.

In any case, the precision of the pattern drives the precision of the response. More data equals a more precise pattern, which equals a more precise response. Effective AI is directly proportional to the rows and columns, or “features,” available to train the models. Data volume and granularity matter, but data volume and granularity in healthcare is quite low when it comes to the digital understanding of patients’ health status—as evidenced by the struggles of IBM Watson.

There are no corpora of knowledge in healthcare equivalent to the collection of knowledge that made Watson successful on Jeopardy. My healthcare provider, and probably your healthcare provider, too, only collects data on me about once per year, or less. That’s not enough of a data sample to inform a precise AI model. One of the most important missing data elements, in terms of value to AI, is patient-reported outcomes. Without patient-reported outcomes, the most valuable AI algorithms to patient care are left in an open-loop status.

We see many AMCs developing their own AI models, particularly predictive models, but lacking the interventions that make them effective. I advocate a pragmatic approach to AI hype, working within the realities of healthcare analytics, up to the leading edge of AI, but not beyond it, where hype exceeds reality.

There are three general categories in which AI can be applied at AMCs: First is imagery analysis, and that’s where hype and reality are most likely to coincide. Second is administrative functions, like rev cycle, billing and supply chain management; there is a lot of untapped opportunity there. Third, and the most overhyped and challenging, is clinical diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In this third area, we are overwhelmed in the industry with clinical risk predictive models, but risk predictions without suggestions for intervention are a liability to the decision maker, not an asset.

At Health Catalyst, we have a library of 20 to 25 predictive models covering topics like patient risk stratification, readmissions predictions, and propensity to pay predictions, so we’re in the game like everyone else. But, we are actively working on AI models to support informed interventions, not just predictions. We’re also building tools to help choose the best AI models for a desired outcome and evaluate all the traditional tradeoffs between sensitivity, specificity, and all that. In any case, we’ve designed DOS to evolve naturally, as the volume and type of data to feed AI models expands, and we’re designing new features in DOS to support the development, deployment and maintenance of AI models in one environment, applying DevOps concepts to AI applications.

AMCs are at the center of this, given their role in clinical trials, device and drug development, etc. What these buzz words really means is, pharma now recognizes that they need to improve their reputation and value proposition; and towards that end, they need data from real-world healthcare operations, not just clinical trials.

The love-hate relationship between the pharma life sciences industry and academic medicine is as old as the first pill. Skyrocketing pharmaceutical costs and a growing distrust towards the pharma industry indicates that healthcare needs to improve for the sake of the patient. From a data perspective, the two worlds need to come together, and the motive for coming together around data can’t be more revenue or profit; there’s no more money left in the economy. It has to be about healthcare value to the patient.

We, Health Catalyst, started a Life Sciences business line that is committed to bringing the pharma and device industries closer to the frontlines of healthcare outcomes by bridging the data trust gap between pharma, providers, and patients. With our healthcare operations background, Health Catalyst can turn real-world evidence into real-world action that directly improves patient outcomes. By bringing pharma and AMCs together through analytics and as a trusted intermediary, we can improve clinical trial design and execution, stimulate clinical innovation, support population health through medication adherence, health economics, and outcomes research; reduce pharmaceutical costs by optimizing prescribing and adherence; and improve drug safety and pharmacovigilance.

In addition to the Analytics Adoption Model, AMCs can use what I’ve described as “The Seven Attributes of a Data Operating System” as a framework for assessing their ability to build their own or evaluate vendors. We defined the attributes as a means of distinguishing a “data operating system” from a data warehouse.

The following are the seven attributes of a data operating system:

In addition to meeting these attributes, AMCs will also need to build or acquire a few other important capabilities:

Modern architectures and design patterns have made future proofing significantly easier. Many of the systems I designed for the space and defense sector over 30 years ago are still in operation today, slowly evolving, piece by piece, never going through a total rip and replace. Likewise, the EDWs that we designed at Intermountain Healthcare and Northwestern Medicine, in 1998 and 2006 respectively, are still operating.

A modern analytics platform, such as DOS, supports a modular evolution of each component, following the best practices of systems engineering that exist today. We are confident that our version of DOS will be operating and thriving at client sites 25 years from now.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here is an article we suggest:

5 Reasons Healthcare Data Is Unique and Difficult to Measure