As value-based care (VBC) definitions and goals continue to shift, organizations struggle to create a roadmap for population health management (PHM) and to track associated costs and revenue. However, health systems can move forward with PHM amid the uncertainty by following the best practices of a path to value:

• Begin with Medicare Advantage—a good growth opportunity with low barriers to entry.

• Focus on ambulatory, not acute, care as it delivers more value.

• Leverage registries based on utilization to identify the most impactable 3 to 10 percent of utilizers.

• Simplify the physician burden by focusing on reasonable measures.

Download

Download

This report is based on a webinar presented by John Moore, CEO and Founder of Chilmark Research, on August 7, 2019, titled, “Population Health Management: Path to Value.”

Regulatory changes demand that providers take on more risk and have the appropriate IT infrastructures to do. Therefore value-based care (VBC) and population health management (PHM) are increasingly integral to future healthcare technology and market trajectories. Meeting PHM goals requires significant investment, and organizations are still seeking better understanding of the PHM landscape, how to derive benefit from it, and how to achieve positive ROI from investments in PHM strategies.

Population health management is a proactive, data-driven strategy focused on improving the health of a given population by a defined network of financially linked providers, achieved in partnership with the community. Organizational efforts around PHM have escalated in response to nationwide value-based initiatives stemming from the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 and the shift of population risk from payers to providers. Providers are moving to more proactive care models to reduce costs and improve quality.

Health systems need four core elements to enable PHM:

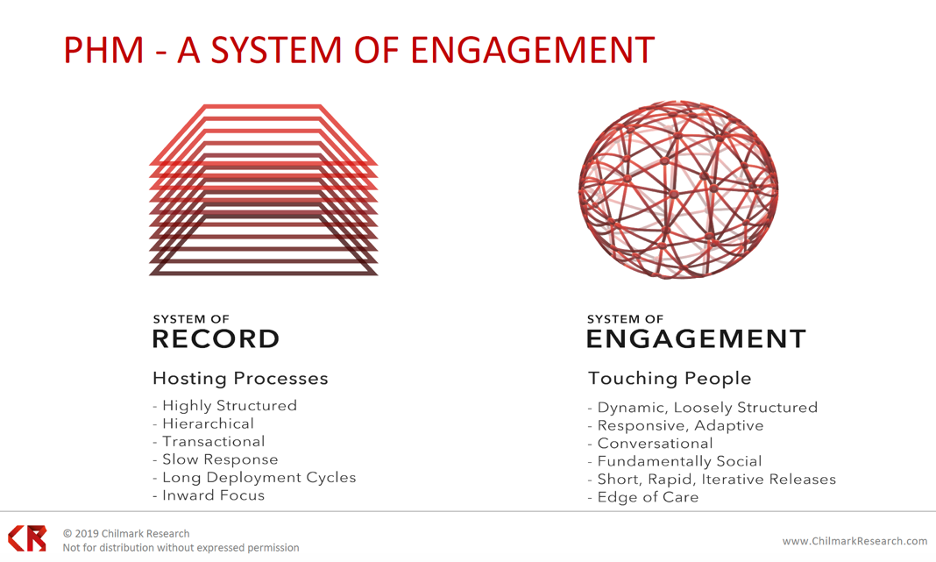

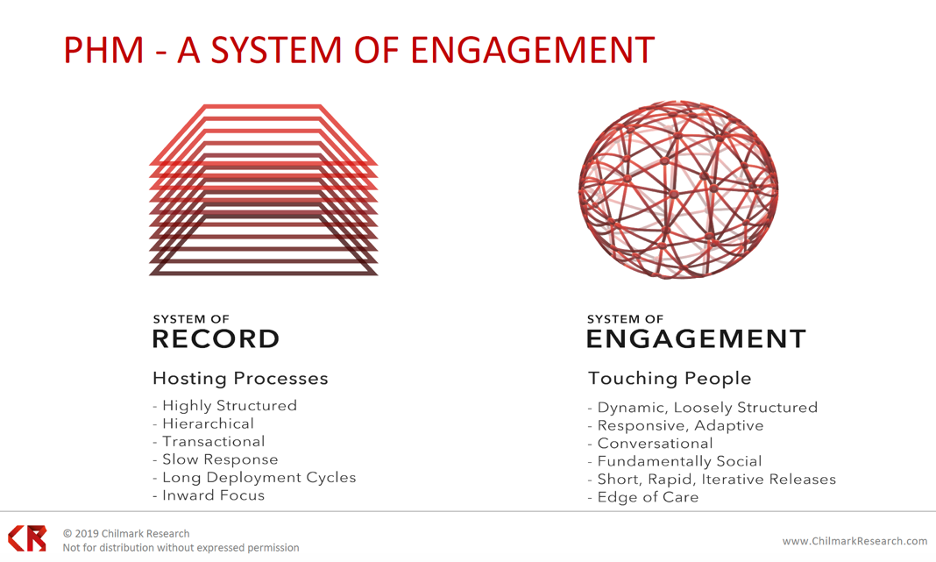

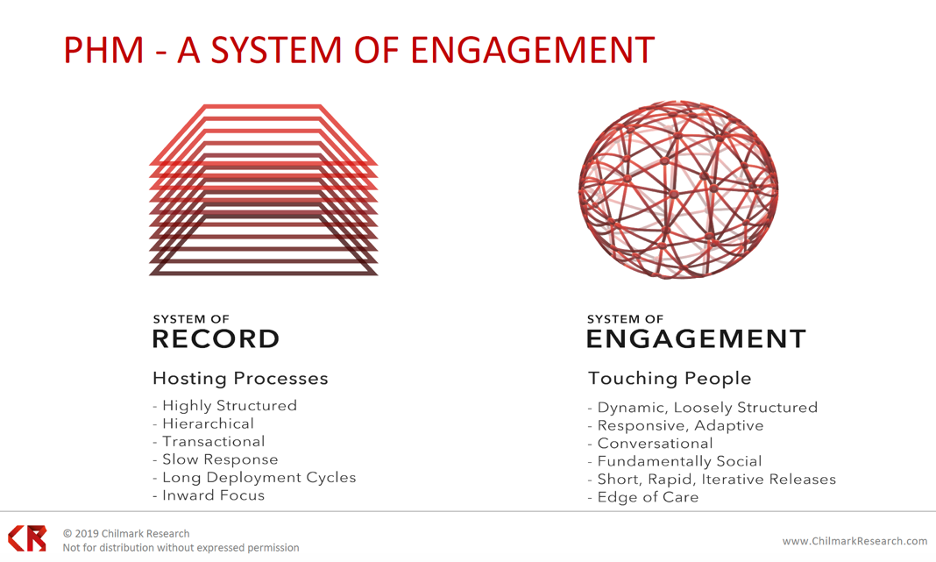

Following the four pillars above, population health is a system of engagement (Figure 1). The systems of record (the basic software/hosting processes) tend to be hierarchical, transaction based, and slow to respond and have long deployment cycles and an inward focus. Systems of engagement, on the other hand, provide outreach from the clinical workflow to the population in the form patient-facing information. The system-of-engagement approach helps patients make appropriate health decisions, which ultimately extends to how a health system manages a population within a region or community.

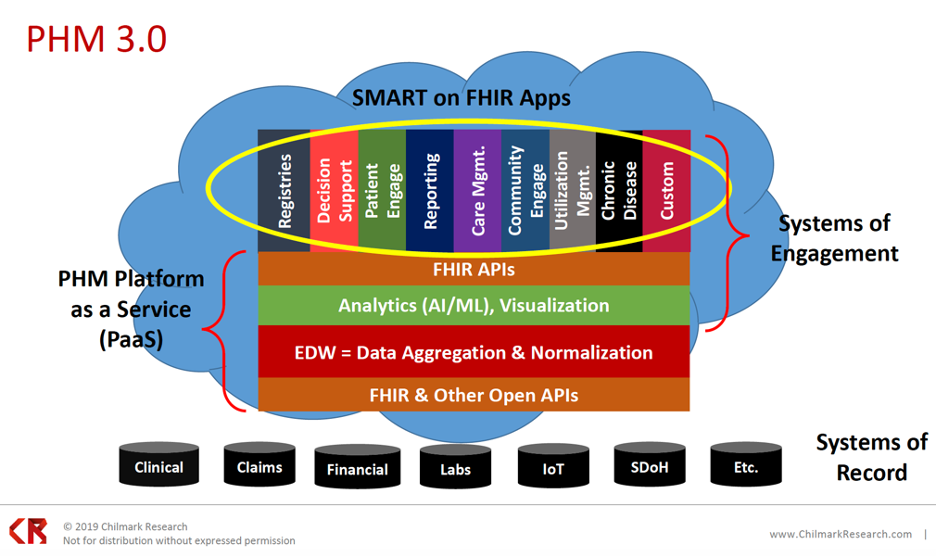

Population health management capabilities have steadily expanded over the decades from PHM 1.0 (mid 1990s) to PHM 2.0 (around 2012) through PHM 3.0 (2020 and onward):

Even with the PHM evolution to 3.0, key challenges remain in carrying out a population-focused strategy:

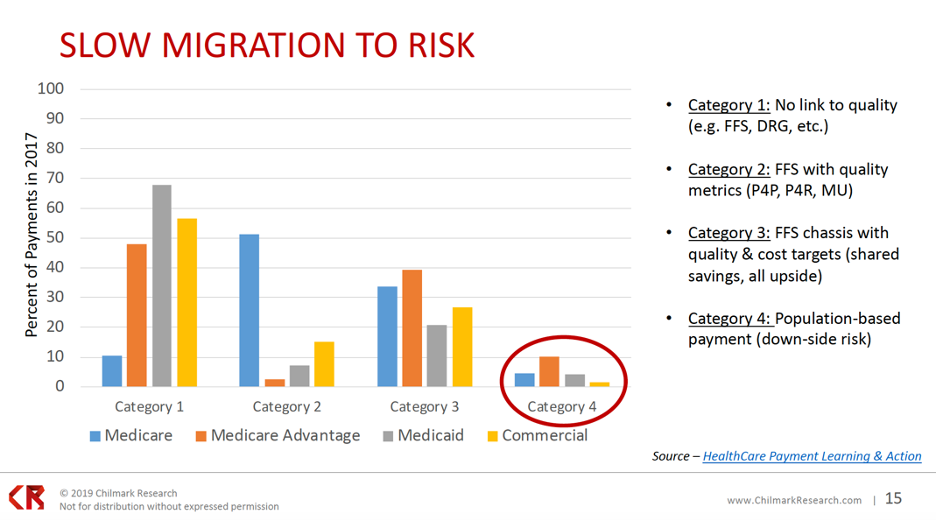

While PHM has matured from 1.0 to 3.0., the industry migration to risk has moved slowly since the passage of the ACA in 2010, with fee-for-service (FFS) payments still comprising a majority. Figure 3 shows the percent of risk-based payments in 2017 with four payment categories, listing those with any downside risk in category 4. As the graph below illustrates, as of 2017, a lot of payments don’t include some form of downside risk. Most payments have been category 1 through 3 (standard fee-for-service or a fee-for-service chassis with some quality metrics and some cost targets, as in category 3).

Organizations continue to struggle with their ability to take on risk, especially downside risk in value-based payment models. In a 2016 survey on the state of population health, organizations largely predicted they’d be ready to assume risk by 2018. Between 2016 and 2018, however, respondents’ actual readiness to assume risk fell from a 61 percent confidence rate to 25 percent.

With market uncertainty, FFS remains the primary source of healthcare revenue in 2019, as organizations decide whether to invest in VBC or wait for more direction from the federal government. A bigger shift towards VBC requires restructuring, resources, and executive commitment, as leadership must drive cultural realignment from volume to value.

During the slow migration to risk, three major PHM adopter profiles are emerging:

About 5 percent of PHM adopters are the true innovators. They have a strategic focus on population health and see the ability become value-based focused as an organizational core competency. Innovators have a strong focus on cost because they’ve already assumed quality as a competency and are now turning towards structuring their cost profile.

At 38 percent, the early-mid adopters are process focused, with an eye to workflow. They’re looking at how to get insights into the point of care and enable the physicians, clinicians, and community to make informed decisions. Early-mid adopters are implementing benchmarks of baseline agnostic measures with strict, but reasonable, quality measures. If a payer comes to them with measures that exceed those benchmarks, they will walk away from the contract. Early-mid adopters focus less on cost and more on quality.

The late PHM adopters, making up 57 percent, are tactically focused. They’re taking a contract-by-contract approach to population health and VBC, typically starting with their own employee base.

In spite of VBC slow progress, notable trends are driving providers to take on more risk:

The current CMS and HHS administrations are actively pushing providers to take on risk. The most recent rules for the Medicare Shared Savings Plan (MSSP) position ACOs as the pathway to success, giving providers only one year of basically no risk (just upside) on these contracts; after the first year, providers have to assume downside risk as well.

While CMS is tightening the window for organizations to assume risk, it’s also proposed more flexibility via waivers, allowing organizations a little more choice in how they meet the guidelines. Other flexibility initiatives include talk about relaxing the Stark Law (the physician self-referral law) and some states moving to a capitated model for Medicaid.

Medicare Advantage is currently an active market, as over 50 percent of new beneficiaries are choosing it, which is accelerating partnerships between providers and payers. Payers are actively looking for providers they can partner with on Medicare Advantage to improve Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) scores, as by improving those scores, organizations can maximize incentives.

Commercial (employer-supported) ACOs are relative newcomers to the payer scene, but employers are looking to support ACOs, basically doubling current contracts by nearly 50 percent. Employers are also increasing direct contracting with providers, particularly providers with high-performance networks (networks that can deliver value).

Even with the above drivers pushing healthcare towards risk, getting value out of PHM differs among regions in the nation. The local and regional stakeholders (employers, payers, etc.) will define the value equation by their region, leaving an inconsistent understanding of ROI across the country.

In a 2019 Chilmark Research survey, over 22 percent of respondents said they were getting positive ROI from their PHM/VBC investments, two-thirds said they expected positive ROI over the next one to three years, and only 11 percent said they had no plans to measure ROI. However, when the researchers drilled down and asked organizations how they defined ROI, they learned that organizations were omitting some costs in ROI calculations, such as all the PHM investments they’ve made to date.

With varying definitions of value and ROI, measuring whether PHM is delivering value—if it’s paying for itself—is difficult. Perhaps as organizations fully commit to VBC, ROI will become more attainable.

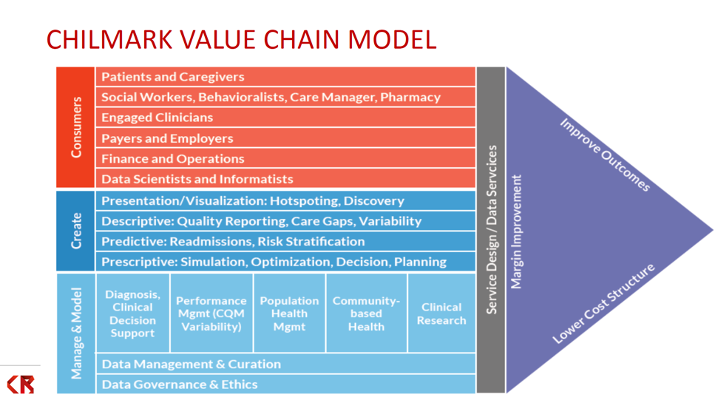

For now, value is a moving target, with definitions and goals shifting by the year. Even CMS can’t promise consistency, making it difficult to create a roadmap and a repeatable way to track cost and revenue to understand ROI. Health systems overall, however, seem motivated to continue with value, as VBC activity research shows. To move forward amid the uncertainty, organizations can use a value-chain model and best practices to ensure a successful path to value. The Chilmark value chain model (Figure 4), for example, can help organizations begin mapping how they would approach population health and, ultimately, VBC, with the goal of improved outcomes and margins and lower cost structure.

Organizations that have launched PHM tend to agree on a set of best practices:

While the healthcare shift to value is slow, it’s increasingly evident as key drivers push providers towards risk and adopters emerge. Health systems need PHM strategies to succeed under VBC, but in an uncertain regulatory environment, organizations have struggled on the path to value their PHM initiatives. Organizations can navigate the uncertainty by following a value chain model and best practices for a PHM strategy.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest: