Healthcare today is in the midst of a massive transformation. The opportunities for improvement are great if healthcare systems can do the following:

• Reduce clinical variation.

• Reduce rates of inappropriate care and care-associated patient injury and death.

• Follow accepted best care practices.

• Eliminate waste.

This article covers the different types of waste in healthcare systems, ways to reduce them, financial alignment around waste reduction opportunities, and the importance of reducing clinical variation. The core driver of healthcare systems must be improving clinical quality. Almost always, with proper clinical management, better care is cheaper care through waste management.

Download

Download

This report is based on a 2018 Healthcare Analytics Summit presentation given by Brent C. James, MD, MStat, former Vice President and Chief Quality Officer at Intermountain Healthcare.

A hundred years ago, the healing professions went through a massive transformation in healthcare delivery. William Osler, a Canadian physician practicing at Johns Hopkins University and the founding father of internal medicine, was one of the architects of that transformation. In 1916, when the transformation of healthcare was underway, Osler spoke to a group of new physicians at Phipps Clinic in England. He said, “I’m sorry for you, young men and women of this generation. You’ll do great things, you’ll have great victories, and, standing on our shoulders, you’ll see far, but you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution to have seen a new birth of science a new dispensation of health, reorganized medical schools, remodeled hospitals. A new outlook for humanity that is not given to every generation.”

When he gave that speech, Osler and his colleagues were establishing the current model of care delivery that is still used today. Now, the healthcare industry is currently experiencing a change of a similar magnitude. With that challenge comes massive opportunity, one in which today’s pioneers will be able to echo Osler’s words to the next generation. While healthcare organizations need to reduce costs to maintain viability, the change must come from clinical quality as the core business strategy.

One such massive opportunity is reducing unwanted variation in clinical practice. Variation in clinical practices undermines the goal of providing high-quality care for all patients. High rates of inappropriate care, where the risk of harm is inherent in the treatment, can outweigh any potential benefit. This leads to preventable care-associated patient injury and death due to an inability to do what healthcare providers know works.

Investigators began to apply rigorous clinical research measurement methods to routine care delivery performance. In doing so, they discovered that these systems identify evidence-based best practice protocols that could be incorporated into the clinical workflow. Data from these best practices are then fed back through a continuous-learning loop that enables healthcare teams across organizations to constantly update and improve the protocols, ultimately reducing waste, lowering costs, and improving access to care and patient outcomes.

In the 1980s, healthcare organizations began using activity-based costing (ABC) systems that had been successful in other industries. At the same time, The Dartmouth Atlas, developed by Jack Wennberg, worked to measure and identify significant geographic variations in care.

In 1986, Intermountain Healthcare localized the otherwise broad approach of the Dartmouth Atlas within its own healthcare system, incorporating ABC principles and standardizing the tool across the system. Intermountain’s Quality, Utilization and Efficiency (QUE) studies applied rigorous clinical research methods to routine care delivery performance in six clinical areas at the health system’s inpatient facilities on a local level.

The QUE studies identified massive variations among physicians and care teams, even within a single hospital with all physicians following Intermountain’s best practice protocols. That variation was true for all six areas measured: transurethral prostatectomy, cholecystectomy, artificial hip joints, bypass graft surgery of the heart, permanent pacemakers, and community-acquired pneumonia. Each study showed a roughly two-fold variation. In the case of the QUE studies, the amount of variation within a single hospital is larger than the amount of variation that Wennberg and others were showing across hospital referral regions. That large amount of variation inside each individual facility represents a huge opportunity for improvement.

Healthcare falls short of its theoretic potential for the following five reasons:

1. Massive variation in clinical practices. With variation so high, this essentially guarantees that not all patients receive high-quality care.

2. High rates of inappropriate care. Care is deemed inappropriate when the risk of harm inherent in the treatment outweighs any potential benefit.

3. Unacceptable rates of preventable care-associated patient injury and death. In a profession aiming to “First, do no harm,” these are situations where patients are placed in harm’s way in violation of health professionals’ core ethical commitments. In fact, research shows there are 210,000 preventable deaths each year in the U.S. alone.

4. Inability to follow best care practices. A study of recommended care processes found that adults surveyed received recommended processes only about half of the time (54.9 percent). If healthcare practitioners can achieve miracles in care delivery, and that happens only half the time, imagine what could happen if best care practices were achieved in close to 100 percent of patients?

5. Vast amounts of waste. The U.S. spends $3.6 trillion annually on the delivery of healthcare and as much as $2 trillion of that amount may be quality-associated waste.

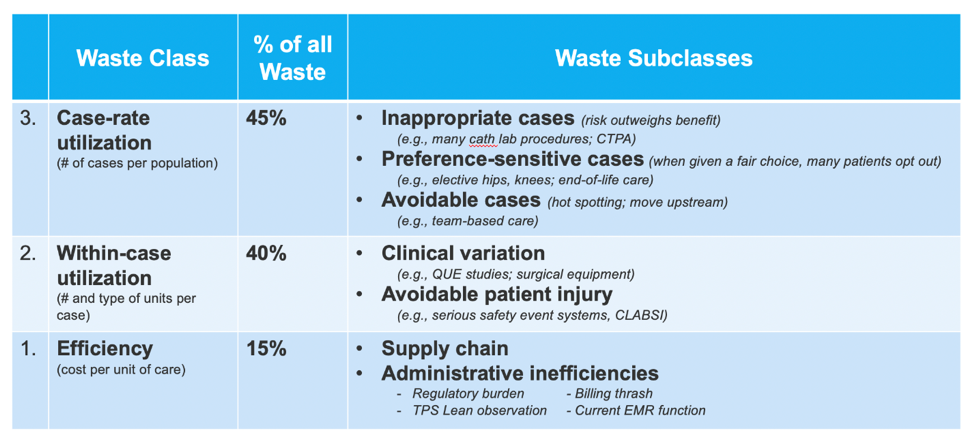

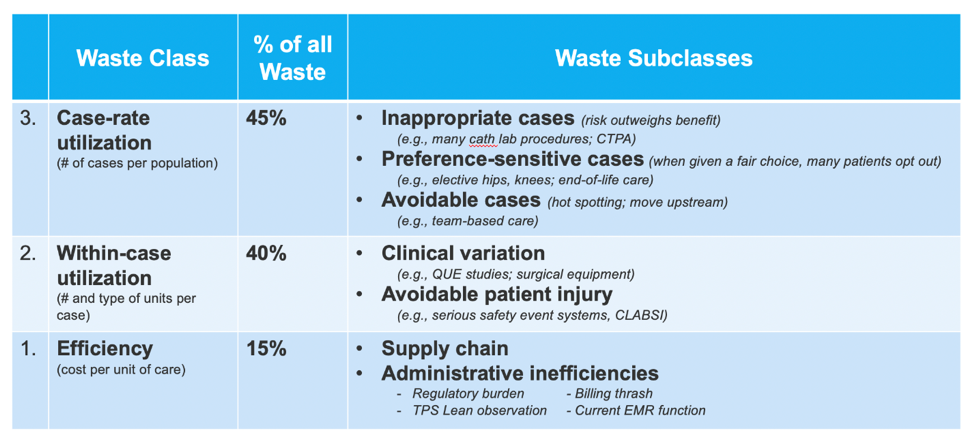

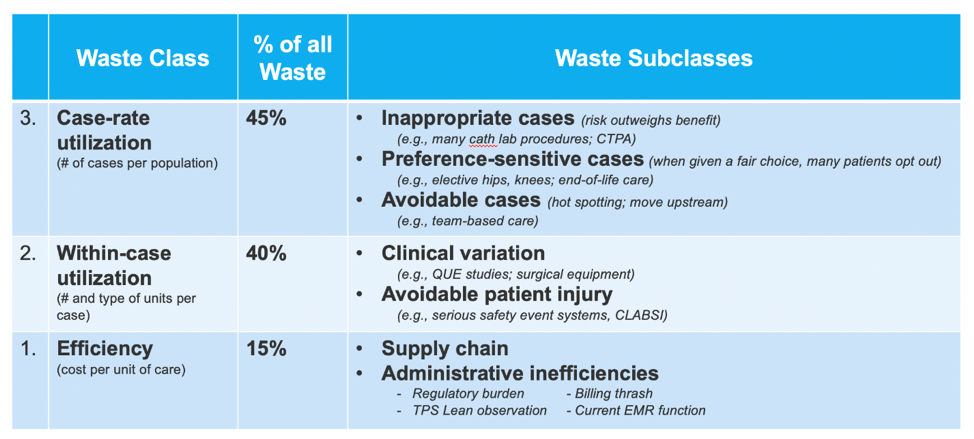

All five of these factors add up to vast amounts of waste in healthcare, leading to spiraling prices that continue to limit access to care. According to the National Academy of Medicine, between 35 and 50 percent of all money spent on care delivery today in the U.S. is technically waste or non-value adding from a patient’s perspective. Some examples of quality-associated waste include:

Reducing waste is critical to the survival of healthcare systems. The interesting thing about tacking waste reduction is that health systems need to make an investment in order to make system-wide changes that extract waste. Typically, health systems use revenue growth as their primary financial strategy. In the average system, a net operating income drop below three percent can cause failure. The response of many healthcare systems is to build more hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, or other specialty care buildings. However, the financial leverage that this mindset can deliver via increased revenue is merely a five to nine percent contribution for each case added. In contrast, the financial leverage from waste elimination is a 50 to 100 percent contribution to the operating margin for each case avoided. Reducing waste dwarfs all other financial opportunities in healthcare and in today’s society.

If health systems, want to survive, they need to focus on waste reduction. Some examples of ways to reduce waste include the following:

Each of these categories has breakouts that healthcare systems can drill down to the level of action and put a plan in place to reduce waste.

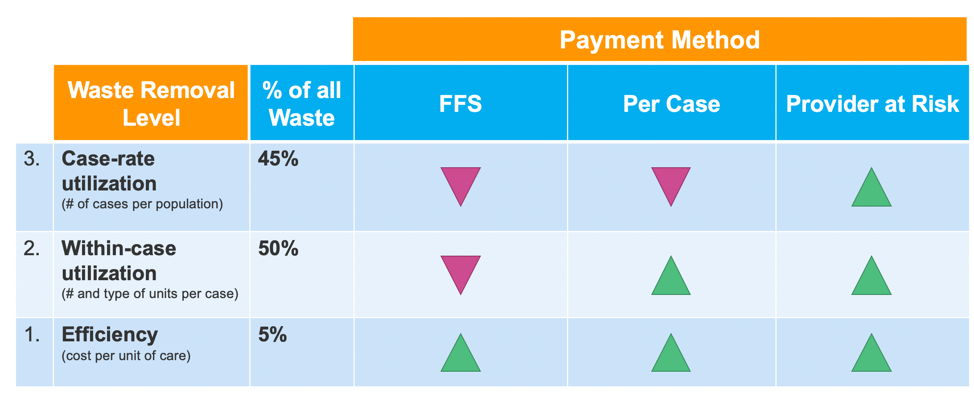

Reducing waste requires financial alignment. As mentioned above, reducing waste requires an investment and a commitment to make system-wide changes that are necessary to get to the root of the problem.

“The Case for Capitation” in the Harvard Business Review, shows how the ways to reduce waste by level shown in Figure 2, correspond directly to payment mechanisms (Figure 3). The pink arrows indicate the drop-in revenue is higher than reduction in costs–a paved road to financial dissolution. The green arrows show the alignment of financial incentives. In Figure 2, the far-right column shows that the per case payments are lower risk opportunities than fee-for service, but if a healthcare system wants to tackle case-rate utilization opportunities, that comes with some financial or shared risks. The bottom line being, the group that makes the investment must harvest sufficient waste savings to ensure financial survival and contribute to operating margins. It also shows that population health-based payments are the only method that allows the health system to benefit from reducing all three categories of waste.

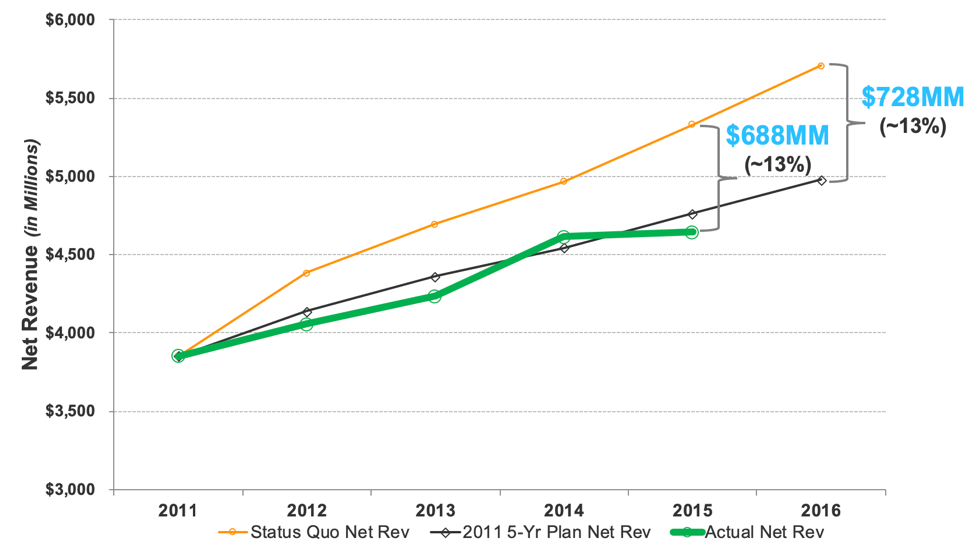

The financial impacts of clinical quality alignment are real. Intermountain Healthcare reduced its total cost of operations by 13 percent through waste reduction over a four-year period. The opportunity is there and achievable for health systems that make the investment.

Lessons learned about possibilities for healthcare delivery are as follows:

Knowing these lessons, it’s interesting to speculate on what the future of healthcare holds. The two predictions with the greatest implications are: pay-for-value will continue to grow and healthcare IT will mature.

The implications for increasing pay-for value are:

What maturing healthcare IT will mean:

Additionally, quality will become the core business and that will drive bottom-line cost control and waste in a provider at risk financial environment. To conclude, an old Yiddish proverb sums it best: “Better has no limit.” Harkening back to the William Osler quote, healthcare providers and administrators have only begun to discover how good the future of healthcare might be. Each person in the industry should be tasked with the mission of creating a new system and paradigm shift of such great magnitude that future generations can only begin to imagine the possibilities.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download the presentation highlighting the key main points.

Click Here to Download the Slides

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/BO0ayxkaPozBA8