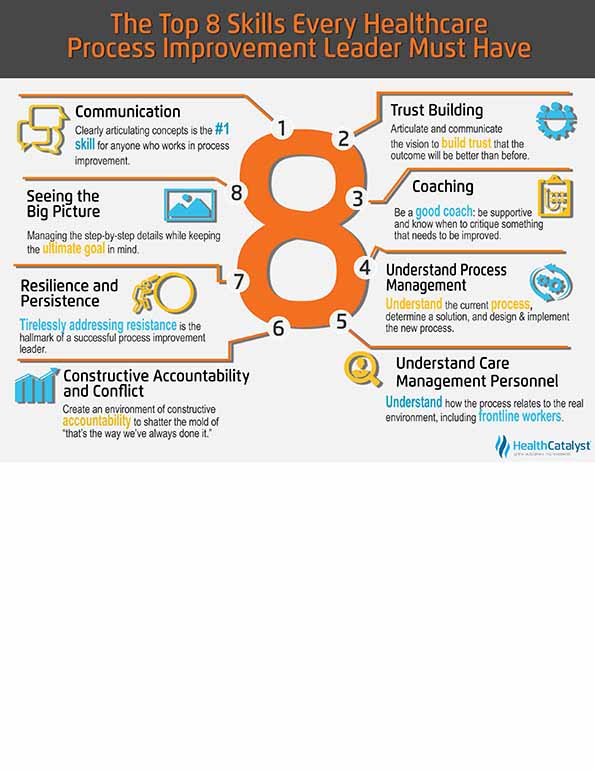

Healthcare process improvement leaders not only have to be a jack-of-all-trades, but they need to be a master, as well. This is one of the most important leadership roles in the healthcare system with responsibilities that can ultimately end up saving lives, improving the patient experience, improving caregiver job satisfaction, and reducing costs. Although there are many others, these eight skills are the most critical for the efficient, and ultimately, successful process improvement leader:

1. Communication

2. Trust Building

3. Coaching

4. Understanding Process Management

5. Understanding Care Management Personnel

6. Constructive Accountability and Constructive Conflict

7. Resiliency and Persistency

8. Seeing the Big Picture

Along with the right training, education, and sponsorship, it’s easy to see why this role blends many elements of art and science.

Successful healthcare process improvement leaders need to operationalize information. That is, you must be able to take data and derive knowledge from it through analytics. It’s how you move from an academic endeavor to attaining results. To make a difference in your organization’s improvement, you must move beyond ideas, toward something much more practical.

To illustrate the importance of process improvement, consider how a mere 0.1 percent inaccuracy in healthcare translates to 107 incorrect medical procedures every day, and 20,000 incorrect prescriptions every year.

1. Communication

Communication is the number one skill required of anyone who works in process improvement. You must learn to articulate ideas and concepts verbally, in writing, and by listening. So much of what leads to success in this arena is the ability to listen very well, hear what’s happening, and combine that with what the data reveal. This tends to create better solutions because the people working on the process every day typically understand the problem and many times know the answer. By asking them to participate, you glean their knowledge. Often simply by listening and asking open-ended questions, you help the team work out a solution for themselves. Sometimes, you are just there to provide the wherewithal for approval.

Communication is typically defined to include articulation, verbalization, coaching, and cheerleading. But the more interesting point is the consistency of letting people know what’s going on all the time, or at least as much as possible. This is what starts to build trust.

2. Trust Building

Process improvement leaders ask teams to change, whether big or small, to do something different from what they’ve always done before. Build and share the vision for where the team is going, articulate and communicate it, and eventually build to where the team trusts that the outcome will be better than where they are today. They need to trust the leader, think of you as part of the team, and know you have their back.

3. Coaching

The successful process improvement leader is a good coach. You come from a change management perspective, so you understand how to help people grow from whatever they are doing today, to whatever they will be doing in the future. This typically means filling a knowledge or training gap where the organization has to move from the current state to future state. A successful leader needs to encourage people that they can complete steps a, b, and c to get outcomes x, y, and z. You must be able to step back and look at the process or situation from an outsider’s viewpoint, to help individuals on the inside see what that new world needs to be and how they can get there. Like a coach of a sports team, you need to be supportive, but also be able to critique if something needs to improve or be done differently. This is a critical success factor.

4. Understanding Process Management

How does work…work? It’s not such a silly question when looking at the critical nature of workflow and methodology used in problem solving. I’ve seen a million different approaches to any given problem. Some are good in their own way, and some may present a new set of problems. But without a fundamental understanding of the work process, or methodology that one must go through to study a problem, identify a solution, and then implement the solution, it becomes very difficult to get anything truly accomplished. It becomes an academic, rather than an actionable, exercise.

To be able to change a process, you need to be able to understand workflow that is occurring, and the individual steps that make up the process. The process improvement leader needs to understand the current process (current state), and once a solution is determined, to design and implement how the process should happen (future state.) The ability to breakdown the work processes into their individual steps is a critical skill to help identify the root cause of the process failure, and ultimately develop a solution.

The successful process improvement leader takes a scientific approach to resolving a problem or situation, or making something better, as far as an outcome goes. This means understanding that data—the right data, in the right hands, at the right time—is required for every scientific measure or approach. With data, you can make informed decisions, gain understanding, and allow your organization to implement true fixes to the problem. Without data, you are merely guessing at what steps to take. Having the data component allows you to address the real problem, rather than conjuring what the real problem might be.

5. Understanding Care Management Personnel

The successful leader understands the frontline work processes and demonstrates an ability to work with and through others. From the process improvement perspective, successful leaders understand not only the process, but how it relates to the real environment. You have steps A to Z to help diagnose and dissect an issue and come up with a resolution. But you also need to have an understanding of the people involved, what the issue is becoming, and how that progress is going. You involve the people who are working on the issue on a daily basis: doctors, nurses, radiology/surgical/lab techs, housekeeping, finance…location within the facility isn’t an issue. Involvement is. The people who need to be involved are those who are really doing the work that is being analyzed. Fundamentally, the methodology and tools used to solve a clinical issue are the same as a non-clinical one. But like in any project, some steps will require different amounts of work, and some tools will be better than others in analyzing the situation. We need to follow the workflow to determine the right skill set, knowledge, and expertise required to solve the problem. Clinical or non-clinical, their knowledge and expertise is needed to understand the issues, and resolve the problem. Getting the right people involved is the key to improve the overall process.

6. Constructive Accountability and Constructive Conflict

As difficult as it may seem while in the thick of it, if you create an environment of constructive accountability and conflict, you will have a more positive outcome than if you don’t. You need to understand how to communicate using a contrastive approach because by creating an environment of accountability and conflict, in some respects, you create an energy that eventually shatters the mold of “that’s the way we’ve always done it.” Only then can you design a new mold to create the new process. Without this constructive energy, people won’t move into this new world.

7. Resiliency and Persistency

Change management is very complex. Everything won’t always go perfectly; in fact, it probably never will. Like Sisyphus and his boulder, there will be resistance along the way. This resistance appears in different ways: people don’t want to change, the status quo is fine; someone wants to challenge what’s historically been done by a certain skill set; people are trying something that nobody else have ever done before; the literature says this is a great thing to do; the organization is trying to implement a theoretical model.

There are lots of reasons why resistance surfaces, but the ability to address them and continue with renewed energy hour after hour, day after day, and week after week is the hallmark of a successful process improvement leader. Also, the organization must allow the team that’s trying to implement a new solution to get to a tipping point where results start to happen and they can see the progress they’ve been trying to achieve. This demands resilience to stand up to a lot of negative feedback and the influential people who say this can’t work for a million different reasons.

The successful leader says “instead of telling me all the reasons why it’s not going to work, tell me why it will work!” You need to look at it from the opposite extreme, and many times, this starts to break up the logjam. One must keep pushing, otherwise the energy in the room will ebb, and it will be much easier to fall back into the status quo. And if the data showed that something can be made so much better, why would you want to sit back and let status quo take over? The leader has to be persistent and keep pushing forward to make change happen.

8. Seeing the Big Picture

Process improvement experts understand and analyze detailed steps, but you also keep the bigger picture in perspective. You have short-term milestones and big-term goals that you need to hit. It is very easy for individuals and teams to “get lost in the weeds” and begin questioning “why are we doing this?” But as a leader, it is important to see the big picture, and to connect the intricate details to the ultimate goal to help the team keep moving. You have to be organized so you can manage the step-by-step details, while also making sure the compilation of all those tasks are matching and meeting the ultimate goal.

Good process improvement professionals are always thinking like process improvement professionals: you always look for a better way to do something. You see the inefficiencies and inconveniences, almost the negative side, of how life is going on, because you know it can be better.

For example, it might drive people nuts to hear complaints about the lines in grocery stores or for movie tickets. But there has to be a better way. If people are standing in a line, then that’s a problem (unless they are at Disneyland where lines sell merchandise). But typically, if lines exist, it tends to be a signal of a failure somewhere.

If you are very good at process improvement, you come upon this type of thinking somewhat naturally. You think about how to be more efficient or how to make something easier for the customer, worker, or for everybody in general.

That said, there are definitely tools, techniques, and methodologies that are very teachable to anyone who is willing to listen and learn. It’s a typical scientific method to identify the potential problem, research it to understand what’s going on the current state, develop a new solution, test it, implement it, and then complete the PDCA cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act).

There is formal training available: Lean Six Sigma, scientific method, schools of engineering, and business analytics. All of these components add to the process improvement leader’s supporting toolbox.

Process improvement leadership is a very teachable science, but those who are very successful, fill in between all the mechanical steps with an art component. That’s where the super success lives. The science piece is very specific and detailed, but the art part is how it’s applied.

It’s becoming common for process improvement leaders to have this scientific and artistic expertise. Many experts now have Lean or Six Sigma green and black belts, different certification levels. There was a time when Total Quality Management (TQM), Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI), and Continuous Quality Management (CQM) training was sufficient. Now this new approach, which is very similar, but with a few different tools, has the fundamental process analysis methodologies that one needs to understand to help dissect situations and develop solutions.

To give process improvement leaders credibility for what they are trying to accomplish, they should be embedded within operations, reporting to the COO, CNO, CFO, or possibly CIO. In some organizations, this function resides within the Quality department, which is responsible for regulatory and compliance reporting, medical staff committee support, and many other duties. To be successful, the process improvement function needs to have its own identity wherever it sits on the organizational chart.

This position needs flexibility and the capability to work with anybody and everybody within the healthcare system. Sometimes a departmental construct limits the position from being able to work with medical staff or someone else within the organization. So, the position needs to be high enough in the organization to garner clout. But, at the same time, the position cannot be viewed as the right hand of administration, parroting what administration wants. The process improvement leader needs the autonomy to challenge overall processes.

Whatever process is being targeted for improvement, the process improvement leader needs the knowledge of, and access to, the resources required for improvement. Sometimes, this is like being between a rock and hard place, but that can also provide a nice foothold for pushing up to bigger and better things.

If the leader is working on systemwide issues and problems, its best to approach them from a system-level perspective rather than an individual hospital perspective. The converse is also true. Ultimately, it depends on the specific situation to determine whether this position should sit at the hospital or corporate office level. Both can be successful. It just depends on the corporate culture and how much support this position is given within the organization.

Much of this business is about being in the right place at the right time and having an executive sponsor who really believes and understands the intent. Sometimes, the best person or group of people are in place, but without the right support, the results may never show. On the flip side, an average person given the right tools, support, and latitude may be very successful.

The executive sponsor and how the process improvement leader is positioned within the organization establishes your credibility when you go to work on a project.

There are countless examples within our industry of dysfunctional processes or clinical outcomes. This is why healthcare needs to be more perfect than it currently is.

There are so many opportunities to make something one step better. Processes can always be improved and process improvement always continues. Process improvement leaders are undeniably critical to meeting these opportunities.

Technology everywhere is beckoning to improve hospital operations, the patient experience, and healthcare in general. A lot of health systems now have an enterprise data warehouse and accompanying analytics tools that inform operational and clinical process improvement discussions and sustain these improvements over time. These tools just need the right process improvement leader at the helm.

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.