Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and clinically integrated networks (CINs) are two types of organizations working to address the problem of rising costs. As ACOs and CINs continue to evolve, organizations moving into value-based care (VBC) face an ever-changing landscape. This article looks at the evolution of the ACO and CIN models, what new tools ACOs employ today to promote success, and lessons learned from organizations that have succeeded in alternative payment models. It also explores what healthcare experts believe the future of alternative payment models will look like and competencies to develop to meet those changing demands.

Download

Download

This report is based on a 2018 webinar given by Amy Flaster, MD, MBA, Vice President, Population Health Management and Care Management at Health Catalyst, and Jonas Varnum, Population Health Management Consultant at Health Catalyst, entitled, “ACOs and CINs–Where Did They Start, How Have They Evolved, and Where Are They Going Next?”

The current growth rate of healthcare is unsustainable. In fact, it’s the largest driver of federal debt in the United States, with Medicaid placing tremendous pressure on state budgets. Companies that self-insure employee groups are also struggling to balance their budgets as the cost of healthcare grows rapidly.

ACOs and clinically integrated networks (CINs) are two types of organizations working to, among other things, address the problem of rising costs. As ACOs and CINs continue to evolve, organizations moving into value-based care (VBC) face an ever-changing landscape. This article looks at the evolution of the ACO and CIN models, what new tools ACOs employ today to promote success, and lessons learned from organizations that have succeeded in alternative payment models. It also explores what healthcare experts believe the future of alternative payment models will look like and competencies to develop to meet those changing demands. Although this article focuses on ACOs and CINs, these are just two of many innovative payment reform and contract models used today.

In response to growing healthcare expenses and political pressure to reduce costs, healthcare organizations are on a decades-long payment reform journey. A pivotal point in this process took place in 1932, when the Committee on the Cost of Medical Care released a landmark medical study. The report recommended the “integrated practice of medicine rather than autonomous individual sets of practices.” The question of how to achieve this integration has confounded the medical community since that time.

Fast forward to the 1970s, the passage of the Federal HMO Act in 1973 encouraged the growth of prepaid medical groups, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and independent physician associations (IPAs), all of which are the predecessors to today’s ACO structures. At the time, these organizations were constructed as an alternative to existing fee for service medical care, bringing together a range of medical services in a single organization. HMOs would provide these services “as needed to subscribers in return for a fixed monthly or annual payment periodically determined and paid in advance.” These models can stand as early ACOs and the first examples of value-based payments.

The 1990s brought about the managed care era, sometimes dubbed “the managed care revolution of the 1990s.” During this time, insurance companies contracted with providers for capitated payments. At the time, managed care provided little quality assurance or protection in terms of insurance risk, which resulted in public backlash from both patients and providers. Around this same time, the first CINs were born, prompting the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to create standards and provide guidance around clinical integration.

In 2007, Elliott Fisher published the article “Creating Accountable Care Organizations: The Extended Hospital Medical Staff” in Health Affairs, introducing the term accountable care organizations/ACOs, which made its way into the Affordable Care Act. That same year, the IHI developed the Triple Aim framework, placing focus on improving the patient experience, improving the health of populations, and reducing healthcare costs. The Triple Aim, and the subsequent Quadruple Aim, are part of this history, not because they are landmark legislative acts in the development of VBC, but because they have provided a moral compass for healthcare reform. In today’s current landscape, there are over 1,000 ACOs covering 30 million lives. That’s one in 10 Americans. And the journey to VBC continues to evolve.

CMS defines an ACO as “a legal entity recognized and authorized under applicable federal or state laws, comprised of eligible groups of providers that work together to manage and coordinate care for a payer specific population.” While that is the legal CMS definition, there isn’t one standard industry definition of an ACO. ACOs are voluntary or legal entities comprised of groups of doctors and hospitals that share responsibility for both quality and cost for a population. Unlike the traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model, an ACO directly ties payments to outcomes of care and the providers’ abilities to deliver care in an efficient manner.

There are a number of clinical and administrative commonalities across ACOs, including Medicare ACOs, commercial ACOs, and Medicaid ACOs. Clinically, ACOs share a number of features:

ACOs also share the following administrative features:

Although ACOs share these clinical and administrative features, contracts can differ considerably based on the type of ACO (i.e., Medicare, commercial, or Medicaid). While it can be difficult to make generalizations because of this, one common theme among all ACOs is the shared contract goal to reduce a population-specific total cost of care. Though contracts can vary greatly in the specifics, common components include the following:

ACOs should ask the following question when reviewing or negotiating a contract:

Although both ACOs and CINs are collaborative entities with similar goals, are are significant differences in the way they are structured. While an ACO is a contract-based term with payment tied to outcomes, a CIN is the organizing body that can support multiple contracts. Another way to view a CIN is the platform upon which providers can form an ACO.

The FTC defines a CIN as a “structured collaboration between physicians and hospitals to develop clinical initiatives designed to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare services.” Clinically integrated systems are recognized by the FTC and allow joint managed care contracting in order to accelerate improvements in healthcare delivery. The designation of a CIN allows groups the following benefits:

Supplemental to these core qualities are four key principles of every CIN:

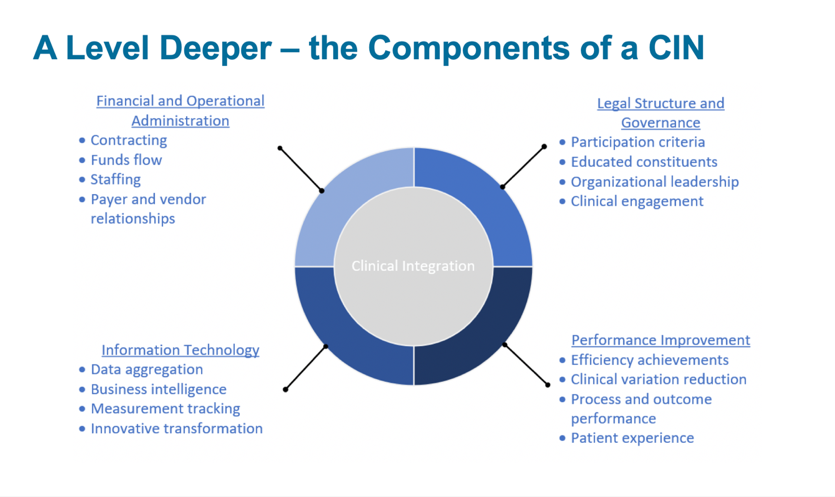

In addition to these four main components, CINs allow for greater coordination across four main areas of the integrated network: financial and operational administration, legal structure and governance, information technology, and performance improvement (Figure 1).

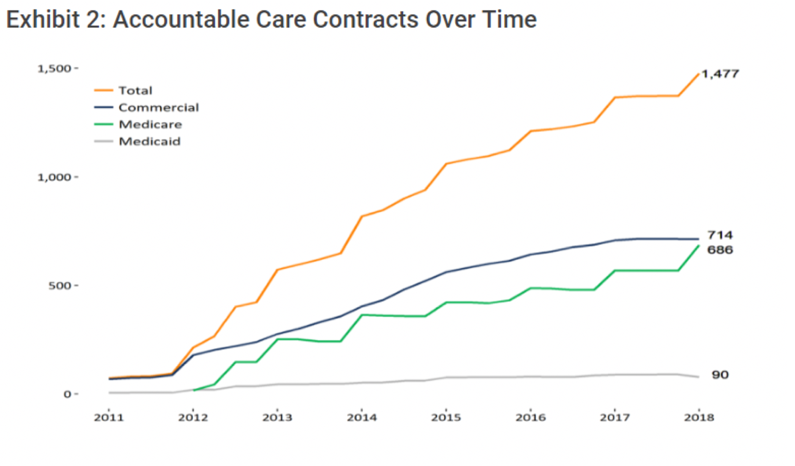

ACOs are growing, with over 1,000 ACOs covering more than 32 million lives. Historically, commercial ACOs have primarily driven this growth, but that number flattened in 2019 while Medicare ACOs and, to a lesser extent, Medicaid ACOs, continue to rise steadily (Figure 2).

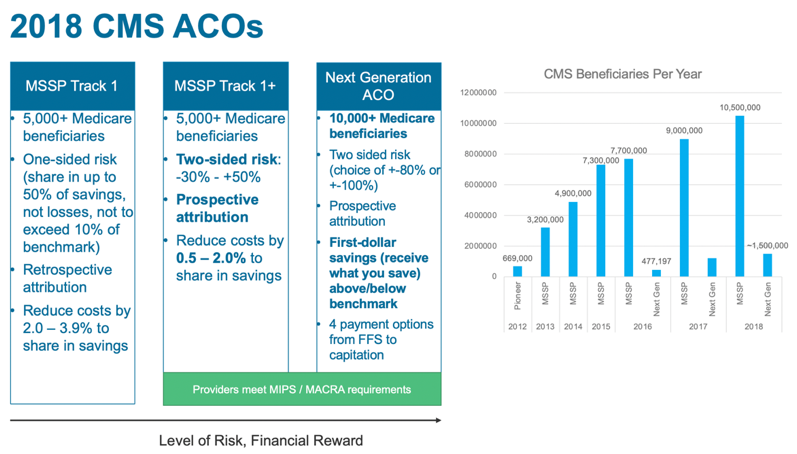

In addition to the recent rise in Medicare ACOs, there has been significant growth in Medicare ACO models that involve more risk. In Figure 3, the illustration on the left side shows the least risk bearing of the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACO tracks, moving toward Next Generation ACOs–the most sophisticated and highest risk bearing of the ACO models.

The bar graph to the right shows enrollment per track by year, illustrating significant adoption with more than 10 million beneficiaries enrolled in MSSP and a steady increase of enrollment in Next Generation ACOs. Interestingly, 21 organizations opted into downside (or two-sided) risk CMS ACOs in 2018, without prior CMS ACO experience, indicating that organizations aren’t necessarily starting with the lowest risk model. These MSSP tracks provide increasing levels of potential bonuses for organizations that keep spending below targets and include repayment penalties for higher than expected spending.

Looking at these numbers, it’s clear that ACOs are moving toward more risk for greater financial rewards. But, what’s the next for ACOs? CMS Administrator Seema Verma said, at an American Hospital Association Annual Membership Meeting in May 2018, “We are working for competition and better value by moving away from a fee-for-service approach, to a system that is value based and that rewards value over volume. We also want to think about models that create a true competitive market where providers compete for patients on the basis of price and quality, and moves the government out of the business of setting prices. … We will also make sure that our beneficiaries have incentives to seek value when they obtain care.”

Similarly, Adam Boehler, Director for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), has taken a hard line approach to ACOs, saying, “If you’re not cutting it, get out of the way, because there are others that will come that will cut it.” These are early signals into a greater emphasis on ACOs having more skin in the game in order to create a truly competitive market. In fact, assuming downside financial risk is a major component of the recent changes to MSSP that became final in December 2018. These changes rename the program Pathways to Success and require most participating ACOs to take on risk within two years in the basic track, placing an increased emphasis on “accountability” in accountable care organizations. CMS plans to implement these changes to MSSP in July 2019.

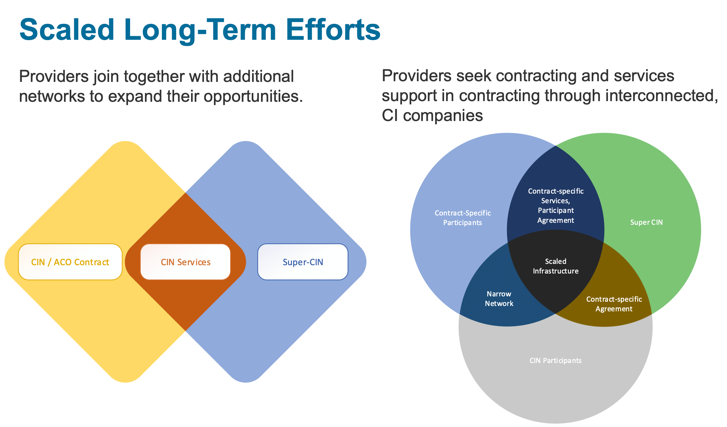

Shifting focus back to CINs, once a group of provider entities has formed a CIN and met the legal requirements, they must move quickly to demonstrate the value of the network. The trend toward consolidation, focus on controlling costs, and shift toward value-based payments are fueling competition and pushing CINs to increase their reach and network offerings. This is resulting in an increase in the Super-CIN model, or multiple CINs under one superseding structure (Figure 1). The goal of these super-CINs is to allow smaller systems to share additional services and contracts while scaling their operational successes and efficiencies. The ability to scale is becoming increasingly necessary as both consolidation and competition increase.

So much discussion of the ACO model and its evolution begs the question, do ACOs work? That is to say, do they improve care and lower the total cost of care? The short answer is that the results are mixed.

According to a recent CMS publication, the data suggests that upside-only ACOs are losing money, driven largely by hospital-based ACOs (as opposed to physician-led ACOs that did save money). CMS data also shows that two-sided risk ACOs are cost-saving. Possibly more telling than which ACOs are losing money and which are gaining is the fact that the actual net impact is relatively small. With $49 million for upside-only risk ACOs and $33 million in net impact for two-sided risk ACOs, relative to the total budget of CMS, these numbers are a drop in the bucket.

However, recent medical literature suggests more significant savings from MSSP ACOs, with an article in the New England Journal of Medicine suggesting the MSSP program resulted in a net savings of $256 million to Medicare in 2015. And, a whitepaper published in the National Association of Accountable Care Organizations in August 2018 reports that MSSP ACOs generated a net savings of $541.7 million from 2013 to 2015.

Looking at the evolution of alternative payment models from the early 1930s through HMOs and today’s increasingly sophisticated ACOs and CINs, these provider structures have taken on increasing risk over time. It’s more important than ever to look at key components of success for these risk-bearing groups:

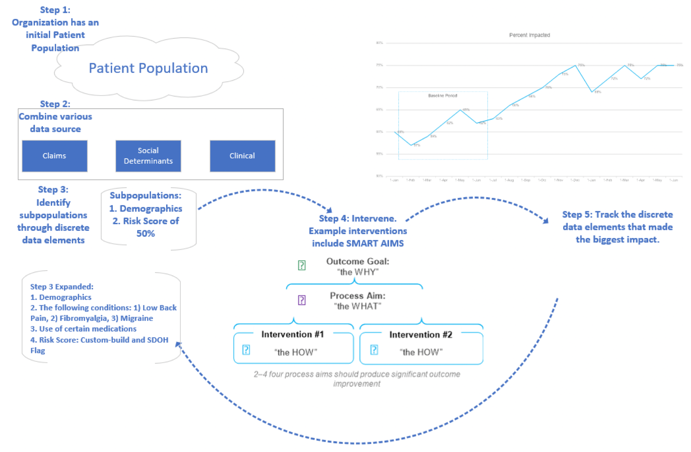

After exploring the evolution of ACOs and CINs, what’s next in the world of alternative payment models? The demands are changing, requiring new competencies to meet them. Below are a few of the changes coming to the alternative payment space:

There’s also an increase in care management outsourcing solutions. While in the past, this has meant billing and technology support, solutions now include a full suite of services. Lastly, is the digitization of care management—which includes patient stratification with machine learning, risk identification for targeted interventions, and telemedicine. These are all exciting developments in care management that will help support evolving care models.

The journey to VBC can be traced as far back as 1932, with many bumps, twists, and turns along the way. And, while the destination still remains out of reach, there’s been a lot of progress in providing better care, reducing the cost of care, and improving the health of populations, aided, in part, by the transformation of payment reform models.

ACOs and CINs are evolving, and there is more change on the horizon. The types and structures of these organizations continue to shift in a constantly changing landscape. ACOs and CINs must develop new tactics and employ new tools to adapt to changing regulations, increased competition, and more discerning consumers. A move toward strategic contracting, payer and provider integration, Medicaid expansion, evolving care management models, and increasingly sophisticated data are all likely to influence the future of ACO and CIN models. As accountable care models continue to transform, organizations that embrace risk to provide true accountability are likely to lead the way for value-based care.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download the presentation highlighting the key main points.