Research projects that 2020 healthcare industry losses due to COVID-19 will total $323 billion. As patient volumes fall and pandemic-related expenses rise, health systems need a strategy for both immediate and long-term financial recovery. An effective approach will rely on a deep, nuanced understanding of how the pandemic has altered and reshaped care delivery models. One of the COVID-19 era’s most impactful changes has been the shift from in-person office visits to virtual care (e.g., telehealth). Though patients and providers initially turned to remote delivery to free up facilities for COVID-19 care and reduce disease transmission, the benefits of virtual care (e.g., circumventing the time and resource drain of patients traveling to appointments) position telehealth as lasting model in the new healthcare landscape. As a result, healthcare financial leaders must fully understand the revenue and reimbursement implications of virtual care.

Download

Download

This article is based on a webinar by Dan Unger, Senior Vice President and General Manager of Financial Transformation Business at Health Catalyst, titled, “COVID-19 Financial Recovery: The Effects of Shifting to Virtual Care.”

According to a survey from the American Hospital Association forecasting healthcare performance through 2020, inpatient volumes will be down 19 percent and outpatient volumes by 34 percent. Meanwhile, COVID-19 will continue pushing increases in personal protective equipment (PPE) expenses. Together, dropping volumes and escalating costs translate to 2020 projected industry losses of $323 billion.

Federal provider relief funding (e.g., the CARES Act) offers assistance to healthcare organizations. However, while a vital phase of financial recovery for health systems, federal relief will only cover about 50 to 60 percent of health system losses. To regain financial stability, organizations must move through additional recovery phases that will not only help them return to pre-pandemic financial health but also support sustainable, profitable models in the industry’s new normal. Significantly, changes in care delivery options, namely from brick-and-mortar office visits to virtual care options (e.g., telehealth), stand to impact financial recovery by reshaping care models and reimbursement.

While individual organizations face unique challenges, collective experience of COVID-19 impact and pre-pandemic financial health suggests four phases of financial recovery for health systems:

Healthcare industry financial strain become a national concern early in the course of the 2020 pandemic, prompting Congress to respond with $100 billion in relief for hospitals and other healthcare providers. Receiving and accounting for these stimulus funds (including understanding the terms and conditions around qualifying expenditures, risks, and compliance requirements) is the first phase of financial recovery for most organizations. However, as stated above, Congress’s welcome relief funding only covers a portion of the projected industry losses in 2020, making the next three phases of financial recovery at least as vital as the first.

A starting point to recover revenue and accelerate cash is resuming elective surgeries and ambulatory visits, which organizations paused or slowed during the acute phases of COVID-19. These types of non-emergent care are significant sources of revenue for some provider groups or large integrated delivery networks (IDNs), as well as a vehicle for needed patient care.

After restarting paused operations, the next step of phase two is to capture revenue and accelerate cash. Organizations can achieve both through revenue cycle processes such as collecting on outstanding high-dollar accounts, entering charges, and resolving discharged not final billed (DNFB) cases. In short, providers need to get owed cash in the door as quickly as possible.

With potentially lower volumes and lower revenue in the future, health systems must understand and manage their costs. To do so, many health systems will need to invest in key systems and processes:

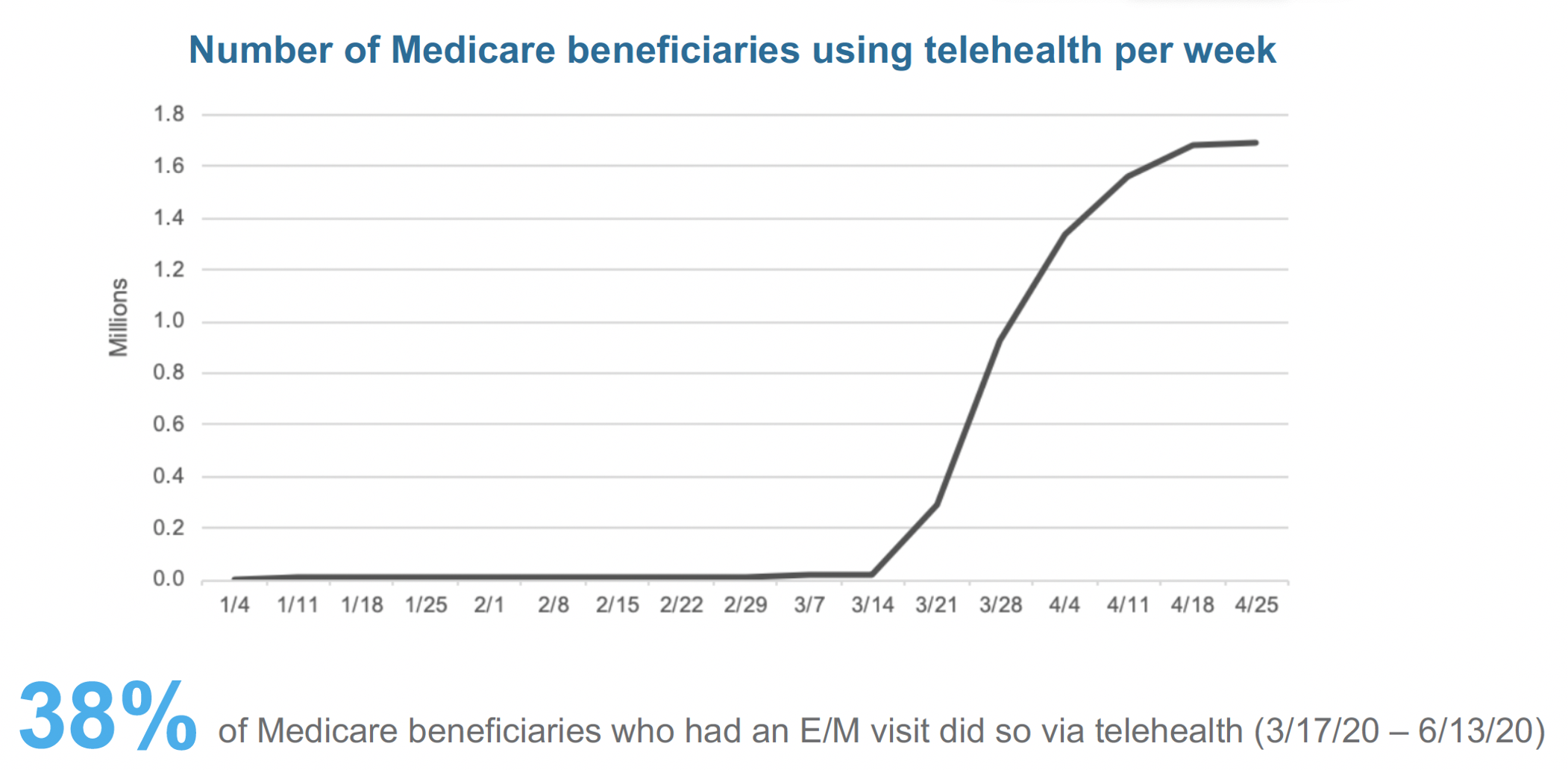

The abrupt drop in patient volume and shift to virtual care makes reinventing health system operations and care delivery mission critical. Before March 2020, Medicare beneficiaries rarely used telehealth. From mid-March to mid-June, however, 38 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries who had an evaluation and management (E/M) visit did so via telehealth (Figure 1). While Medicare is just one portion of the market, this data is part of the trend towards a meaningful increase in virtual care adoption. Telehealth provider Teledoc, for example, reported 100 percent growth in visits from Q1 in 2020 over 2019, with a significant portion of that growth just from the increase in March.

As the rapid growth shows, COVID-19 has pushed a lot of providers to hastily adopt telehealth with little time to prepare and understand the long-term financial implications. While remote care has offered a short-term means of engaging patients with needed care and regaining revenue for non-emergent care, the bigger-picture financial impacts are less straightforward. Healthcare organizations have much to consider as they progress with remote-centric practices.

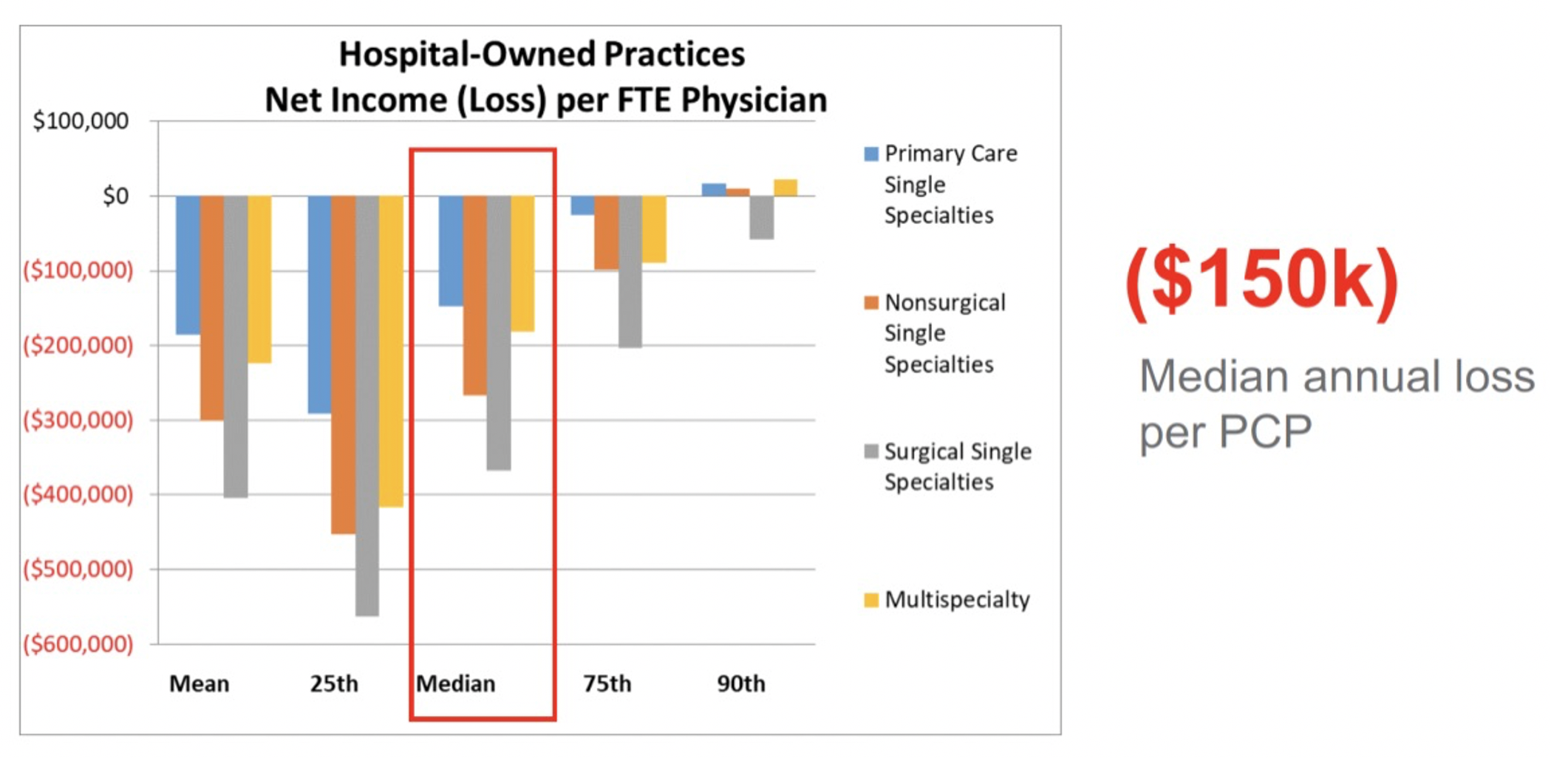

In general, healthcare organizations today lose around $150,000 per primary care provider (PCP), with only the 90th percentile and above breaking even on primary care (Figure 2). As such, employed physician groups are already challenged financially, without the impacts of COVID-19.

With the sudden shift to telehealth, already financially strained providers have entered a new business landscape, as COVID-19 has broken down the competitive barriers between traditional providers and more modern telehealth and disruptive care delivery companies. There’s a lot of movement looking to take traditional providers’ business, and these newcomers are often operating beyond the confines (rules and regulations) of traditional healthcare.

Healthcare’s new competitors fall into three main buckets:

Breaking out of healthcare’s usual rules and regulations, Teladoc, Doctor On Demand, Go Forward, and Crossover Health have business models that overlook coding, CPT codes, and modifiers, and other procedures traditional organizations must follow. Amazon, Walmart, and CVS, on the other hand, have traditional straightforward pricing, which bears watching. It’s important to remember that these corporations are large employers—commercial payers that are redirecting care away from the traditional system into their own care delivery system.

As large corporations and other new providers ramp up competition for patients, they’ll also compete with traditional organizations for clinicians. With burnout and job dissatisfaction rising, the perks and benefits of these modern companies pose a threat to health systems. According to an industry survey, 79 percent of PCPs experience some symptom of burnout. Meanwhile, four out of five of the employed physicians say their health system employers are not doing anything to combat it. And because clinicians drive revenue, losing them will impact revenue.

These disruptive care delivery companies are introducing new models of care with a lot of appeal to clinicians. New models offer less hassle, with no coding and documenting for quality measures and the like. There’s often less stress due to lower patient volumes, and with a lot of the concierge practices and even telehealth, clinicians can somewhat choose how much volume they want, as well as more flexibility.

As well as disrupting healthcare delivery models, telehealth also stands to impact healthcare revenue. Clinicians have historically named lower reimbursement as the number one barrier to telehealth. With CMS declaring they’ll pay telehealth in parity for the duration of COVID-19 health emergency, it’s tempting to consider the reimbursement barrier resolved.

Long-term reimbursement parity, however, likely isn’t realistic. CMS typically pays telehealth at 80 percent of the normal visit, so if an organization continues to pay its clinicians on the work RVU associated with the virtual code, it would reduce its margin by 15 percentage points. If organizations have clinicians sit in the clinic and take some of these virtual visits, they’re degrading their margin and receiving lower payment but maintaining their operational expenses.

As outlined above in the new competitor descriptions, many companies already deliver virtual care at a much lower rate or a combination of virtual and direct primary care. With that in mind, insurance companies will not likely pay full price when telehealth uses the same infrastructure as in-person care, and other vendors are offering the virtual services.

In addition to revenue disruption, healthcare faces lower overall reimbursement and higher bad debt. With a predicted 25 to 43 million people losing their employer-sponsored health insurance throughout the pandemic and over the next year or two, 58 to 90 percent of these individuals will either shift to Medicaid or become completely uninsured.

On the cost front, over the last decade or more, many organizations have acquired or built a network of clinics across different geographies and specialties. Frequently, clinicians don’t use all of their exam rooms—not necessarily indicating that physicians aren’t busy, but that the utilization optimization of patient rooms is lower than it could be.

Now, with a 30 percent drop in volume for these already underutilized large assets and a potential 30 percent shift of that volume to virtual care, health systems have considerable fixed assets and pay duplicate for staffing, resources, and equipment they’re not using. As reimbursement goes down and the delivery model continues to shift, organizations can’t sustain underutilization.

Many new models of care don’t have any office space or huge fixed assets. Some competitors, like Walmart or CVS, use office spaces efficiently by locating them in their places of normal business (which generate a lot of money regardless of care delivery). Many health systems will have to revisit their brick-and-mortar footprint and make tough decisions to optimize their clinics. Fixed costs can't be fixed anymore. Lower revenue together with lower cost structures make fixed costs an urgent area of attention.

Physician compensation is the biggest single cost for healthcare organizations, making it a priority area as delivery models shift. As the revenue example showed, the economics and operations of telehealth differ from traditional healthcare delivery. Organizations can’t keep paying doctors on the same model and even the same rate, as they were paying them based on estimated total revenue. Additionally, work RVUs are abstract and misaligned—whether the visit is 5 minutes or 45, reimbursement is the same based on the coded level and billed item. In the future, health systems may have to measure physicians more realistically (something that leads to operations as opposed to arbitrary work RVUs). The work RVU based on compensation plans won't align with telehealth economics or incentives.

With an understanding of the new revenue challenges of the COVID-19 era, health systems can follow six strategies to recover financially and navigate a new healthcare landscape:

Top-line revenue is likely to go down and stay down for the foreseeable future. Organizations must understand and manage your costs and make strategic decisions.

With lower volumes, health systems need to understand their assets and high fixed costs, which requires understanding the utilization of these resources—the market, where the patient populations are, the financials behind the resources, and potential patient impact of addressing them. Organizations need to build a strategy for delivering virtual care and measure how that would impact their overall footprint.

Lowering cost doesn’t mean cutting costs across the board. For example, consider investing in resources like a scribe to help clinicians with notes, which will allow clinicians to see more patients. Understand the full scope of these decisions, because hiring and investing may increase productivity.

Health systems can’t keep paying clinicians the same way when the economics and operations are different. The clinician compensation model needs to be simple, clearly stating what the model incentivizes.

Large employers, and even small ones, will likely move volume away from traditional healthcare systems if they can't keep up from a customer service and patient access standpoint (optimize wait times, scheduling, etc.). Health systems need to revisit their primary care model, start developing direct primary care models for local employers, and better optimize for virtual and in-home care.

COVID-19 has exposed the flaws in the fee-for-service model. As volumes have gone down, traditional health systems and their model of just managing volume doesn’t work.

Systems that have significantly taken on risk will fare better through this pandemic. On the payer side, where they may be 40 to 50 percent of their own volume, and they’re not paying out claims, they offset the lower revenue and volume on the provider side. Instead of grasping onto the fee-for-service world or dabbling in between risk models where there’s only limited upside risk, health systems must understand their costs and the populations they can impact, then take on risk accordingly.

Financial recovery for health systems from COVID-19 likely won’t look like a return to a pre-pandemic healthcare business climate. Health systems with need to evolve from their older revenue structures and assumptions and financial practices to adapt to new types competition and consumer expectations, as well as shifting infrastructures. With several elements at play, the industry move towards virtual care will impact revenue streams the most. Thorough understanding of healthcare’s new financial layout and of the financial implications of the move towards remote care delivery will help organizations adapt and succeed as the healthcare economy finds its new normal.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download the presentation highlighting the key main points.

Click Here to Download the Slides

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/6ucpsdIZFA4d21