According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, health equity is achieved when everyone can attain their full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position of any other socially defined circumstance.

Without health equity, there are endless social, health, and economic consequences that negatively impact patients, communities, and organizations. The U.S. ranks last on measures of health equity compared to other industrialized countries. Healthcare contributes to this problem in many ways, including ignoring clinician biases toward certain populations and overlooking the importance of social determinants of health.

Fortunately, there are effective, tested steps organizations can take to tackle their health inequities and disparities (e.g., incorporating nonmedical vital signs into their health assessment processes and partnering with community organizations to connect underserved populations with the services they need to be healthy). Some health systems, such as Allina Health, have achieved impressive results by making health equity a systemwide strategic priority.

Download

Download

Health inequities—defined by the World Health Organization as systematic differences in the health status of different population groups—have been in the national spotlight for years, which isn’t surprising given that the U.S. ranks last on measures of health equity compared to other industrialized countries.

Health inequity is a multiple-industry issue with significant impacts (health, social, economic, etc.) on people and communities. Racial health disparities alone are projected to cost health insurers $337 billion between 2009 and 2018.

Healthcare organizations are increasingly making health equity a strategic priority, with varying degrees of success.

How can we tell if health equity has been achieved? “When everyone has the opportunity to attain full health potential, and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance,” according to a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF)-commissioned Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity report (a year-long analysis by a 19-member committee of experts in national public health, healthcare, civil rights, social science, education, research, and business).

Many healthcare organizations, such as Allina Health, have initiated efforts to improve health equity by making it a systemwide strategic priority and investing in the right resources, infrastructure, and programs, which we’ll outline in this article. Other systems, however, are still largely unaware of the inequities and disparities within their walls.

Healthcare has a long way to go to effectively address health inequity, but there are evidence-based approaches to start tackling—or continue the battle against—health inequities. This article explores approaches, both simple and complex, health systems can implement to work toward restoring health equity.

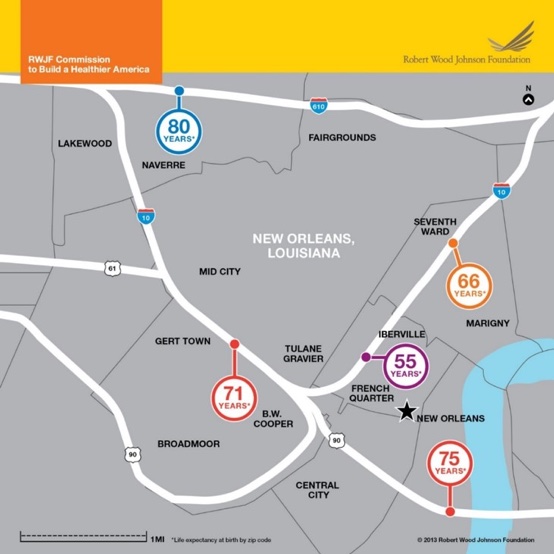

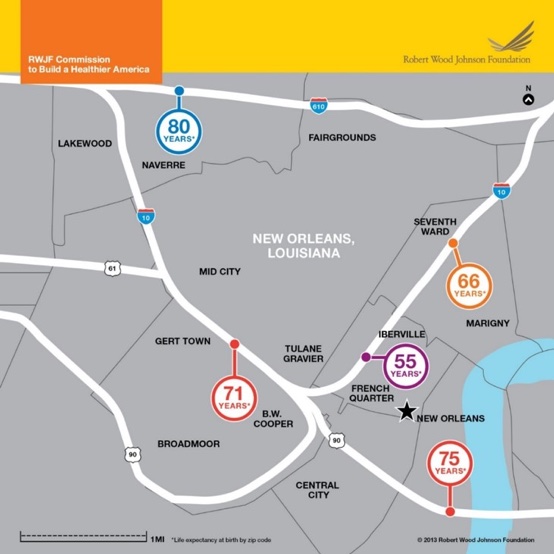

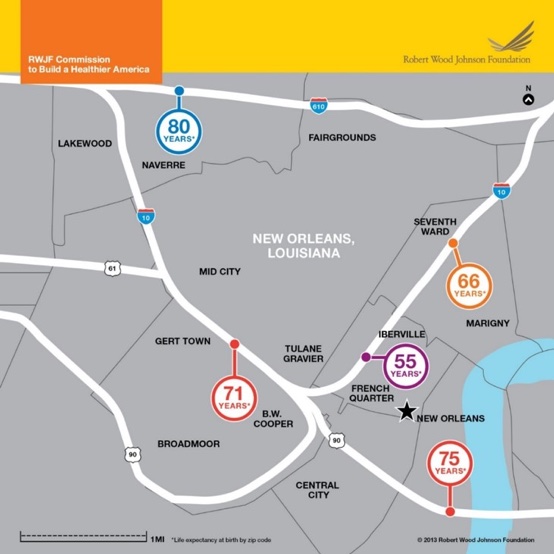

Why are racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. disproportionately affected by poor quality of healthcare? Why are African American infants 3.2 times as likely to die from complications related to low birthweight than non-Hispanic white infants? Why is there a 25-year difference in life expectancy for babies who live just a few miles apart from each other in New Orleans (Figure 1)?

We can start to answer these questions by understanding what causes health inequity, as described in RWJF’s Communities in Action report:

Health inequities are the result of more than individual choice or random occurrence; they are the result of poverty, structural racism, and discrimination. Health systems are just one cog in the wheel of the health inequity issue, but the role they play in the problem is a big one.

Looking at race- and ethnicity-related disparities, for example, differences in access to care, receipt of needed medical care, and receipt of life-saving technologies for certain populations “may be the result of system-level factors or may be due to individual physician behavior” according to an NCBI article. The article states that “patient race/ethnicity has been shown to influence physician interpretation of patients’ complaints and, ultimately, clinical decision making.”

The literature shows that clinicians have biases toward certain populations that impede their ability to provide effective care. Over time, these biases become institutionalized and harder to eliminate. Given that the perceived quality of healthcare (or lack thereof) can significantly impact health outcomes (e.g., adherence to medical advice, cancer screening recommendations, and medication regiments), many health systems find themselves in a self-perpetuating cycle of health inequities and poor health outcomes. Health systems exacerbate their health inequity problems when they don’t have the required data (e.g., socioeconomic) or healthcare delivery structure to discover and correct disparities.

Given that health disparities are shaped by multiple determinants of health (social, economic, environmental, structural, etc.), achieving health equity requires engagement from not just healthcare, but also education, transportation, housing, planning, public health, and many other industries and businesses. Achieving health equity is a communitywide effort.

IHI says “health care professionals can—and should—play a major role in seeking to improve health outcomes for disadvantaged populations.” Healthcare organizations committed to outcomes improvement must also be committed to health equity, and their first step is making it a systemwide, leadership-driven priority.

The Health Equity Must Be a Strategic Priority article outlines five ways health systems can make health equity a core strategy:

Making health equity a strategic priority is the first step. Next, healthcare organizations need to tackle the disparities with proven interventions designed for their disadvantaged populations. The RWJF outlines specific steps health systems can take to address disparities:

Let’s take a closer look at how health systems can incorporate nonmedical vital signs into their health assessment processes to paint a more detailed picture of their patients’ health. RWJF’s Time to Act: Investing in the Health of Our Children and Communities report states that adding nonmedical vital signs (employment, education, food insecurity, safe housing, exposure to discrimination or violence, etc.) to existing ones (heart rate, blood pressure, weight, etc.) can help clinicians make better-informed decisions about treatment and care.

The article notes that new vital signs should be objective, readily comparable to population-level data, and actionable.

Adding nonmedical vital signs to health assessments facilitates healthcare and community collaboration by prompting patient referrals to community resources and improving clinician understanding of patients’ lives outside of the hospital or clinic. It’s this blurring of the lines between health systems and community organizations that will ultimately bridge the health inequity gap.

A recurring theme in recommendations to improve health equity is community collaboration. One organization tackling health inequity with a community-based mindset is Health Share of Oregon, a local coordinated care organization (CCO) serving more than 240,000 Oregon Health Plan members. Its community-based approach connects its members with the services they need to be healthy:

Health Share’s The Power of Together: Five Years of Health Transformation, 2012-2017 report details its health equity progress and how its “local communities come together to improve the health and health outcomes of Oregon Health Plan members, while simultaneously contributing cost savings to the system.” Another health system, Allina Health, is also working to restore health equity for its underserved patients.

Illness, disability, and death are more prevalent and more severe for minority groups in the U.S., and Minnesota is no exception to this problematic trend:

In 2011, Minnesota started requiring healthcare providers to collect race, ethnicity, and language (REAL) data. The inequities revealed by this data motivated Allina Health, a not-for-profit healthcare system serving communities throughout Minnesota and western Wisconsin, to take targeted actions to reduce inequities for some of its racial/ethnic minority patient populations.

Allina Health’s approach to tackling its health inequities involved analytics, research, and targeted interventions. Allina Health used analytics to identify opportunities to reduce inequities, including improving colorectal cancer screening rates among its minority populations. Allina Health recognized that, despite having REAL data, its understanding of patient needs and perceptions regarding colorectal cancer screening was incomplete.

To complete the picture of its patients’ health, Allina Health conducted research and focus groups to understand values, beliefs, and barriers impeding certain patient populations from completing the recommended colorectal cancer (CRC) screenings (e.g., concerns about discomfort with the procedure, based on prior healthcare experiences in a patient’s home country where pain medication wasn’t used, a lack of familiarity with the word screening, basic needs, such as food, housing, and bills, may take priority over preventive health treatment).

With an improved understanding of its patients’ health beliefs and needs, Allina Health developed targeted interventions:

Allina Health’s data-driven approach to reducing health inequities is beginning to make a difference: it has achieved a three percent relative improvement in CRC screening rates for targeted populations. And with REAL data embedded in its dashboards and workflow, it can identify and address additional disparities. Allina Health is one of many health systems making progress toward health equity by making it a strategic priority and implementing evidence-based, analytics-driven, community-informed, targeted interventions.

Healthcare organizations can broaden equity’s scope to include more than the health outcomes of the patients they serve; they can use their resources and status as employers to address equity in myriad other ways:

Success in healthcare requires organizations to improve quality and clinical effectiveness while decreasing costs. Healthcare organizations must include health equity as a strategic priority, broaden health equity’s scope, invest in the structures and processes that improve health equity, and dismantle institutionalized racism.

In pursuit of health equity, organizations must also provide culturally competent care to many different patient populations who need clinicians to understand their lives, address their population-specific healthcare needs, change practices to be inclusive, collect data in a non-judgmental way, and build trusting relationships that enable them to openly participate in care—improvement strategies that are driven by a commitment to health equity.

Although the systemic root causes of health inequities and disparities in the U.S. will take time and hard work to eliminate, health systems can start now by making health equity a strategic priority championed by C-suites. Systems can tackle their data-exposed inequities with interventions of varying degrees of complexity, from adding nonmedical vital signs (e.g., employment) to health assessments, to forging and fostering community partnerships.

The statistics speak for themselves: U.S. Healthcare isn’t equitable. Health systems must act promptly and strategically to remedy this nationwide underperformance and demonstrate their commitment to not only health equity, but also healthcare quality and outcomes improvement.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.