Healthcare organizations seeking to achieve the Quadruple Aim (enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and reducing clinician and staff burnout), will reach their goals by building a rich analytics ecosystem. This environment promotes synergy between technology and highly skilled analysts and relies on full interoperability, allowing people to derive the right knowledge to transform healthcare.

Five important parts make up the healthcare analytics ecosystem:

1. Must-have tools.

2. People and their skills.

3. Reactive, descriptive, and prescriptive analytics.

4. Matching technical skills to analytics work streams.

5. Interoperability.

The healthcare industry continues to welcome advances in technology, but data analysts and architects know that better IT tools alone won’t help organizations achieve the Quadruple Aim (enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and reducing clinician and staff burnout). Instead of relying disproportionately on tools, healthcare organizations will reach the Quadruple Aim by cultivating a rich analytics ecosystem—one with a synergy of technology, highly skilled people in analyst roles, and an organization that promotes interoperability.

The woodworking industry provides a straightforward example of a productive ecosystem. The tools and raw materials are different in a woodshop compared to a healthcare analytics ecosystem, but the goal is the same: both entities work to transform something rough and undefined into a valuable finished product.

Woodworking runs as an ecosystem built on a synergy between sophisticated tools, the people who operate them, and an efficient and dynamic process:

In both woodworking and analytics, interoperability is the seamless workflow from station to station or step to step. Interoperability is a function of the shop layout or the analytics organizational structure. If the layout enables projects to progress smoothly between stations, the workflow is efficient and accurate.

Even the most advanced woodworking tools have an operator (just like healthcare IT tools need a skilled data analyst). Both woodworking and data tools are automated to reduce avoidable human error, but neither is designed to operate without human supervision.

To thrive in a value-based, analytics-driven environment, today’s healthcare organizations must function as ecosystems. Like a woodshop, the analytics ecosystem includes a community and its environment functioning as a unit, with each contributor’s (whether human or technology) strength affecting the end product.

Healthcare IT risks isolating itself from the analytics ecosystem by focusing too heavily on advances and new tools, and not enough on the people with the skills to effectively leverage these exciting technologies and the environments in which they work. Like a woodshop without tool operators and an efficient layout, the most advanced analytics tools are useless without skilled people to run them and an organization that supports their work. Five main parts make up the analytics ecosystem:

Human capital is paramount in the analytics ecosystem, and these highly skilled team members need the right tools to turn raw data into actionable insights. Fortunately, the must-have tools in the analytics ecosystem are foundational technologies that many health systems already have:

Health systems must have the five technologies described above to build out their analytics ecosystem; they don’t, however, have to spend an inordinate portion of their IT budgets to do this. Organizations that spend too much on certain tools end up with an imbalance in their analytics ecosystem and executive pressure to maximize that investment; this can lead to misguided recommendations on how the organization uses the technology. Inordinate spending can also lead the organization to neglect other technologies and the people who support them.

Inordinate spending is a common pitfall of EMR rollouts, as some organizations place more importance on the EMR than other tools. While the EMR is critical to care delivery and improvement, it should be a part of the analytics ecosystem, not the entire ecosystem.

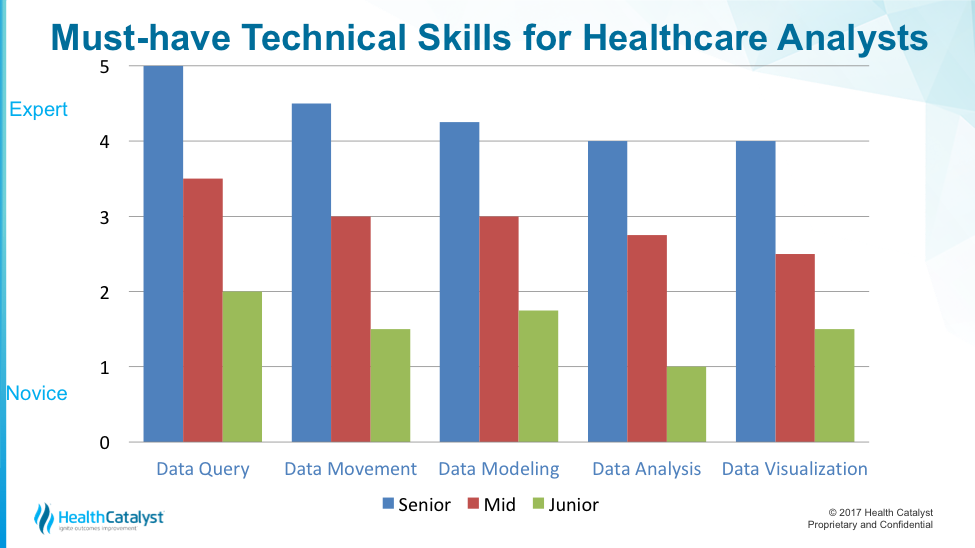

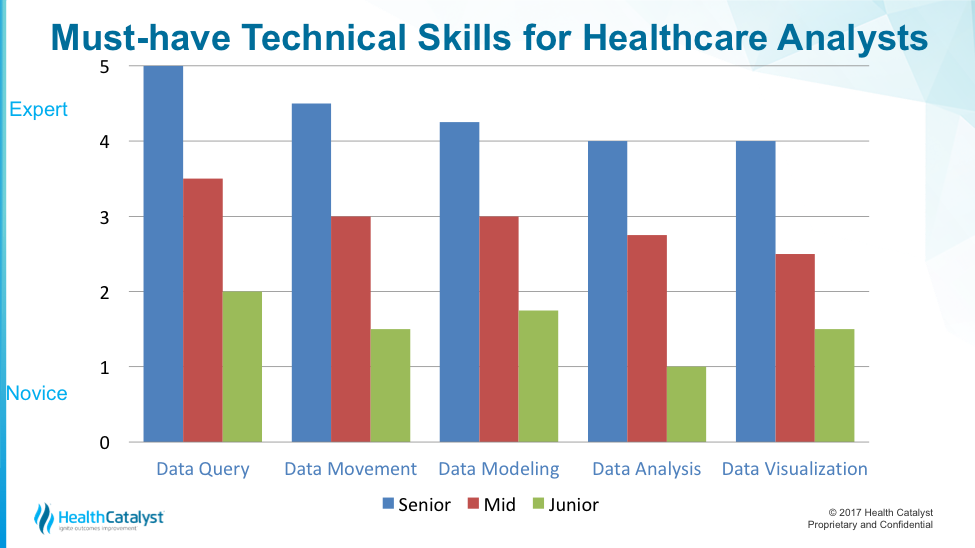

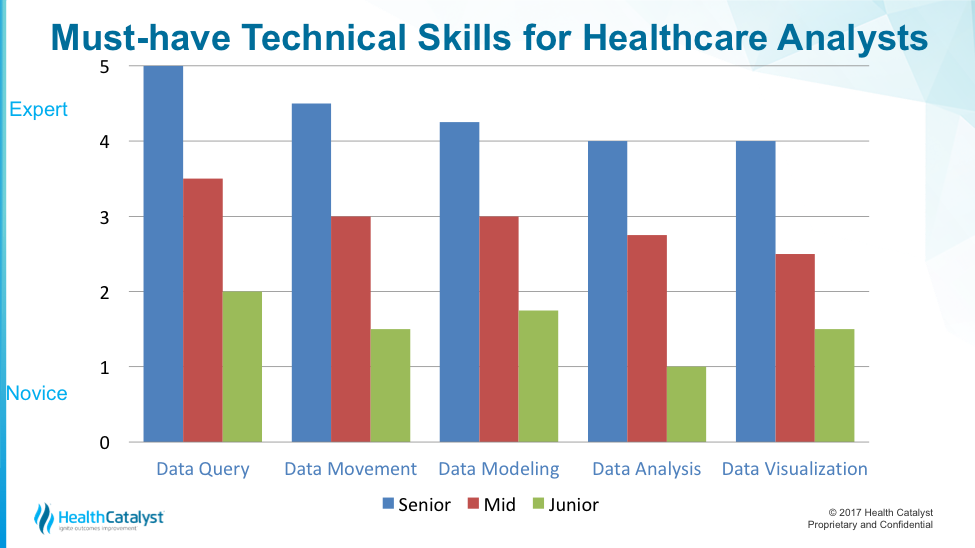

The human side of the analytics ecosystem—the people and their technical skills and contextual understanding of issues and challenges—operate the tools in pursuit of outcomes improvement. These people need five technical skills to drive sustained outcomes improvement:

But technical skills alone provide limited value; they need to be coupled with the knowledge of where to find the multiple rich data narratives that surround a patient encounter (e.g., EMR, costing, and claims data). Add to the skills a deep contextual understanding of what the analytics are measuring, and the skills gain extraordinary value.

Data query, also known as structured query language (SQL), is the language of how data is stored within an organization’s transaction system. Data query allows analysts to explore the relationships between data stored within transaction systems and to establish custom relationships between different transaction systems (e.g., within an EDW or big data in data lakes).

With data query, analysts can move beyond the predefined structures a transaction system comes with, and begin to answer personalized questions about the transaction data. The ability to access and manipulate data within their own systems gives organizations more control over their analytics future.

Data movement refers to the extract, transform, or load (ETL) portion of the technical work. It has two objectives:

Data modeling takes a real-world concept and builds a virtual proxy for it in a database. For example, how might a database represent someone as having diabetes? What would the database use in terms of data to represent such a cohort? Are there specific codes that could be leveraged, such as international classification of diseases (ICD) 9/10 or current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that would qualify or exclude someone from the registry?

Best practice in data modeling stores logic at the database level, making logic visible and accessible to those in the organization who need it (versus performing data modeling in Excel, which has logic visible to only the analyst who created it). Making logic available to subject matter experts for each measured domain, for example, helps health systems design more accurate and robust data models. Transparent logic will also accelerate much-needed engagement from health system professionals. Direct visibility allows them to think or print the logic in the data models and then trust the resulting measurement.

Data analysis is about making information accessible to the right people at the right time. Data analysis relies on data query, movement, and modeling. Meaningful analysis requires deep contextual understanding of the processes being measured. Analysis without contextual understanding puts an analytic effort at risk of long-term credibility issues.

Most healthcare professionals interact with an analytics platform through some sort of visualization, such as reporting, key products indicators (KPIs), dashboards, or ad hoc reports. Data visualization is the vehicle for broad analytics adoption within an organization. Most people who want information to help them do their job don’t have the ability, time, or interest in doing data query, movement, modeling, or analysis.

The visualization step uses underlying data models with their embedded cohorts, their rules of inclusion or exclusion, and their associated metrics. Content is more important than how the visualization looks. Visualizations are only as good as the understanding and the trust of the underlying data.

Figure 1 shows the technical skills data query, movement, modeling, and analysis—described across the X axis—and the level of proficiency with that scale along a Y axis. The colored bars represent different rankings of skills: blue bars for a senior analyst; red for midlevel analyst; and green for each scale of junior analyst.

After establishing an understanding of the technical skills needed for analysts to be effective, organizations must understand the analytics work stream. Figure 2 shows the difference between various analytics work streams (prescriptive, descriptive, and reactive). The rise along the Y axis represents an increase in analytics complexity; the X axis has a compound axis, a combination of the technical skills described above and a contextual understanding of how analysts will use that information.

Reactive analytics show counts of activities or lists of patients. They can include basic calculations on industry-accepted metrics, such as a diabetes admission. Reactive analytics answer anticipated questions; for example, a family practice physician wants to know how many patients with diabetes are on a panel.

Analysts can make minor adjustments to the look and the feel of a reactive analytics report; that’s the extent of customization, however, because reactive analytics are generally confined to a single source of data. Reactive analytics fall short when the report writer doesn’t have a solid contextual understanding of the analytics they’re measuring and why it matters. Reactive analytics explain some of the what has happened or what is happening, but they don’t explain the why—that requires another level of complexity (descriptive analytics).

Descriptive analytics get users much closer to addressing not just what is happening, but also why it happened. Analysts perform descriptive analytics outside the vended systems—often within a dedicated analytics environment, such as DOS or big data environment. Descriptive analytics leverage highly customizable data models. These data models are populated with multiple sources of data (an EMR, claims, external lab, professional billing, etc.), and the models are organized around a common domain. For example, data provisioning and integration efforts in a DOS platform allow a more comprehensive view of the activities within the entire health system. Work in this arena is an ongoing and iterative process.

For example, if a health system is motivated by regulatory penalties to reduce heart failure readmissions, it can look to the CMS explicit definition of cohort and readmission criteria. Descriptive analytics leverages that CMS construct to determine what gets loaded into the data model. Clinicians will scour and approve available sources to capture: diagnosis codes, admit discharge codes, readmission windows, and patient types (as defined by CMS). The analyst will integrate that data together within a custom data model.

Prescriptive analytics make it clear that issue warrants intervention. Once analysts understand the root cause of an issue, they can begin to identify interventions for meaningful change. Sustained prescriptive analytics require technical and domain experts to work side by side in permanent teams.

Each analytics work stream relies on a certain combination of the core technical skills of data query, movement, modeling, analysis, and visualization. Figure 3 shows the required technical skill by analytics work stream.

Certain skills are associated with each work stream. In Figure 3, each bar color corresponds to a skill listed below the graph: data query, movement, modeling, analysis, and visualization.

The graph makes three important points about technical skills in the analytics work stream:

Matching skill with expected labor output is critical in maintaining workflow. Bad things happen when skill and output are mismatched—when team members are in situations where they’re not challenged or don’t have necessary skill to accomplish the work. Team members who aren’t challenged may become disengaged because they’re accomplishing tasks too easily.

A large integrated health system recently worked with a systems vendor to assess its intake process for analytics requests and its organization of analytics work. The health system findings were similar to those from other comparable organizations:

Interoperability is a byproduct of the analytic work streams (the analytics equivalent of the wood shop layout). Each work stream requires the skilled labor to understand not only its role, but also its role relative to the work streams surrounding it, which can only happen if leadership responsible for the overall analytics space can effectively appreciate the analytics continuum: the reactive space, the descriptive space, and the prescriptive space.

Interoperability is a function of the tools and the work stream layout. If leadership fails to identify and stitch together the seams of these analytics work streams, these teams will forever run up against one another in a competitive way, killing analytics interoperability. The organization should reflect years of combined experience and months of deliberate planning.

To thrive in an analytics-driven healthcare environment, organizations must understand four key aspects of the analytics ecosystem:

An effective analytics ecosystem is made up of must-have tools; qualified people with the right skills; reactive, descriptive, and predictive analytics; matching technical skills to analytics work streams; and interoperability. Organizations that understand the value of—and work hard to implement—this analytics ecosystem will change lives for the better by making high quality information available to clinicians and caregivers.

Like the woodshop, a successful healthcare analytics program relies on not only advanced technology, but on the synergy of tools, skilled people, and an organization that promotes interoperability. Tools don’t build cabinets; people do (using tools). Likewise, analytics platforms don’t produce actionable insights; people use these systems to derive knowledge that transforms healthcare.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here is an article we suggest:

Driving Strategic Advantage Through Widespread Analytics Adoption

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.

Click Here to Download the Slides

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/JUCGwSmTqf1DDy