The quality and patient safety movement of the early 21st century called for greater board of trustee involvement in improvement. However, too many health systems still don’t have the resources in place to effectively engage their boards around quality and safety measures.

Six guidelines describe how organizations can better leverage data to inform their boards:

1. Emphasize quality and patient safety goals.

2. Leverage National Quality Forum-endorsed measures.

3. Use benchmarking and risk adjustment to select targets.

4. Access data beyond the EHR.

5. Provide data and information for multiple organizational levels.

6. Develop a board-specific measurement and presentation strategy.

Download

Download

Around the turn of the 21st century, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), formerly the Institute of Medicine (IOM), called for profound transformation to improve the culture of patient safety in two landmark reports: To Err Is Human (1999) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001). These reports accelerated the pace at which health systems began to understand and implement changes to improve the quality and safety of care.

Several impactful movements and influential studies followed the NAM reports, all continuing the appeal for better, safer care and placing accountability for that change on healthcare leaders. Dr. Donald Berwick, former president and CEO of the IHI, added urgency to the need for transformation when he called 2007 the “Year of Governance,” in The Joint Commission Journal on Patient Quality and Safety, placing responsibility for the proper stewardship of healthcare with health system boards of trustees. Leaders needed to own governance, Berwick explained, for improvement to take hold.

Healthcare governing bodies responded to the NAM and Berwick appeals, as well as appeals and arguments from other governing bodies, with regulations to incentivize good health system governance and crack down on inadequate leadership. This article looks at the repercussions for health systems of falling short on governance measures as well as how organizations can engage their boards around quality and safety measures to better meet their communities’ needs.

After Berwick’s call to healthcare boards, regulators soon proved they would take a hard line on governance. For example, in 2008, Modern Healthcare reported that a midsized regional medical center faced intense regulatory scrutiny. The organization’s leadership and board had failed to transparently present and review clinical information and data that would have exposed serious safety issues, resulting in harm to multiple patients. By not understanding their fiduciary responsibilities and requirement to hold leadership responsible for unsafe conditions, the board failed the community it served.

Following patient complaints, state regulators and the CMS cited the medical center for compliance issues surrounding patient care and governance. In May 2008, the state health department discovered that seven leg wound infections occurred among open-heart patients at this hospital; the state then shut down the open-heart program.

In addition, regulators cited the organization for deficiencies in five areas required for participation in Medicare:

With the regulatory crackdown on governance, risks and repercussions of bad governance have significant, costly, and long-term impacts. For example, after the state released the findings of its report on the medical center above, the hospital CEO abruptly resigned, one nearby hospital suspended referrals of cardiac patients, and the hospital’s owner sent staff over 2,000 miles from the corporate office to provide administrative oversight. Such serious consequences placed greater pressure on health system boards to ensure good governance.

Part of the medical center’s correction plan was to ensure that “the [hospital] board is fulfilling its corporate oversight.” The organization clearly hadn’t taken heed of the growing calls within healthcare to improve quality and patient safety. It failed to establish sound governance practices, despite a growing body of evidence that embracing a culture of patient safety was fundamental for healthcare organizations.

While To Err Is Human demonstrated how much needless harm and death occurred in healthcare settings, Crossing the Quality Chasm provided a framework for conceptualizing and defining healthcare quality. This framework, often referred to as the STEEEP framework, laid out six aims for improvement: to provide safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered care. Both reports have continued to inform what effective healthcare governance looks like for health system boards.

Although the healthcare industry has improved since these reports’ publication, a 2018 IHI analysis demonstrated that many health systems still lack sound governance practices and that work to improve hospital governance has moved slowly. Governing bodies continue to rest transformation of care delivery firmly on health system boards.

Notable campaigns since the NAM reports, such as the following, outline board responsibility and continue to serve as guidelines towards better governance:

When the National Quality Forum (NQF) issued Hospital Governing Boards and Quality of Care: A Call to Responsibility in 2004,the NQF strongly encouraged “hospital governing boards to become actively engaged in quality improvement” to place emphasis on the relationship between governance and quality of care.

In 2006, the IHI launched the 5 Million Lives Campaign, which included a call to health systems to join in “getting boards on board.” The campaign recommended that hospital boards get data and hear stories about safety. The IHI also set the expectation that boards “select and review progress toward safer care as the first agenda item at every board meeting, grounded in transparency, and putting a ‘human face’ on harm data.”

The IHI campaign developed six key steps for improving governance:

At its core, the IHI “boards on board” campaign emphasized key elements in creating a culture of patient safety:

The campaign clarified that hospital boards, including non-clinical volunteer trustees, have a fiduciary responsibility to ensure high-quality clinical outcomes in their hospitals. Simultaneously, however, the increasing pace of value-based purchasing and data transparency—largely driven by CMS, TJC, and National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)—have made it difficult for boards to overlook poor quality and safety performance.

Boards increasingly rely on subcommittees of subject matter experts, including the trustees as well as additional independent external experts, to support the various domains of governance (e.g., finance, quality and patient safety, compliance, and strategy) and identify improvement goals. Hospital or health system staff leadership from these functional areas are then responsible to support their respective board committees.

Goal setting for an organization’s quality and patient safety performance follows four steps:

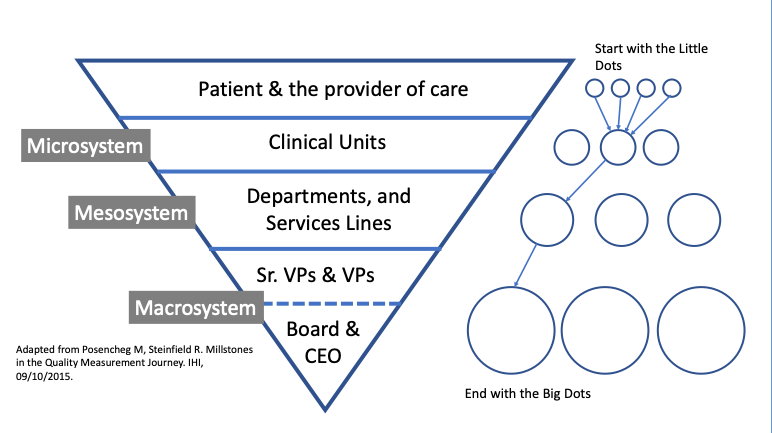

The board will not want to see underlying drivers of the big dot measure, unless the organization is failing to improve. Board committees will, however, want to do deeper dives to understand these drivers. Figure 1 provides a schematic for health systems to view the measurement selection process.

Health system boards can follow six guidelines to select quality and safety measures most likely to support good governance and drive improvement for their organizations:

Quality and patient safety goals should easily represent at least half of all measures the board reviews. Typically, an organization will track 10 to 20 objectives. As Table 1 shows, boards can use the STEEEP framework and big dot approach to guide measure selection:

STEEEP FrameworkMeasure ExamplesSafeSerious safety events (hospital acquired infections [HAIs], serious reportable events [SREs])

MortalityTimelyMedian time from ED arrival to ED departure of admitted ED patientsEffectiveReadmissions

Evidence-based measures and protocols (e.g., sepsis protocol adherence)

Preventable hospitalization EfficientLength of stay

Cost per case

Per-capita cost

Time to next available appointments

Patient flow measuresEquitableTimely ambulatory carePerformance stratified by race and ethnicityPatient CenteredPatient experienceTable 1: Measure examples.

The NQF itself does not develop its own measures; other organizations (e.g., the CMS, TJC, and the NCQA) develop measures of accountability for accreditation purposes. Many organizations select measures endorsed by the NQF consensus development process and link these measures to the six aims of the NAM’s Quality Chasm report or the IHI’s Triple or Quadruple Aim. Some boards of trustees have actually made it policy to only use NQF-endorsed measures for quality and patient safety objectives, when available.

Specialty societies, such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology, often submit their measures to the NQF for endorsement. The NQF established committees of nationally recognized experts to review specific measure sets. Thus, NQF-endorsed measures have not only gone through an internal review and development process by the developer, but also get a second review by a NQF’s independent experts. Selecting NQF-endorsed measures reduces the internal debate over the validity of measures within health systems.

Meaningful targets are critical. Most boards and CEOs aspire to achieve top performance, but not all measures have a meaningful benchmark. A true benchmark looks at top performers and understands how their process led them to outstanding outcomes. Healthcare providers often simply look at top decile or top quartile performance and strive for that goal without breaking down the process changes required to achieve a better outcome.

There are a few rules to keep in mind:

A report for the board quality and patient safety committee and the board of trustees requires data from multiple source systems. Although the dramatic growth in EHR usage has yielded an abundance of rich clinical data, an EHR cannot provide all the information a board of trustees needs to see. For example, patient safety data is often collected in separate event or incidence reporting systems; infection data may reside in a distinct surveillance system, and data as part of the revenue cycle process, as well as collected from claims, is also important.

Boards also expect patient experience of care (satisfaction) from multiple settings:

The analytics team needs a robust enterprise data warehouse (EDW) or an even more sophisticated data platform, such as the Health Catalyst® Data Operating System (DOS™) to meet the needs of the board. Otherwise, the analytics team will spend much of its time hunting for data and producing reports out of different systems. An integrated data platform will increase the timeliness and consistency of data to provide accurate reporting from across the enterprise.

Health system analysts and leadership need to present information to multiple levels in the organization. To determine if its objectives are trending in the correct direction, the full board will typically focus on a single report that includes each of the system’s year-to-date performance for the system’s or hospital’s annual objectives, along with a trend line, spark line, or control chart. Staff will also need to provide an interpretive narrative of the findings for each aim they analyze.

While the board will focus on big dot measures, board committees may also want to understand the organization’s outcomes improvement strategy, especially if the organization is falling short of goals. In a multifacility organization, the subcommittee will also want to determine if certain hospitals, clinics, or other entities are not performing at the same level of the system. Reports that summarize information across multiple facilities run the risk of masking a single facility’s poor performance, so reports must drill down from the system level.

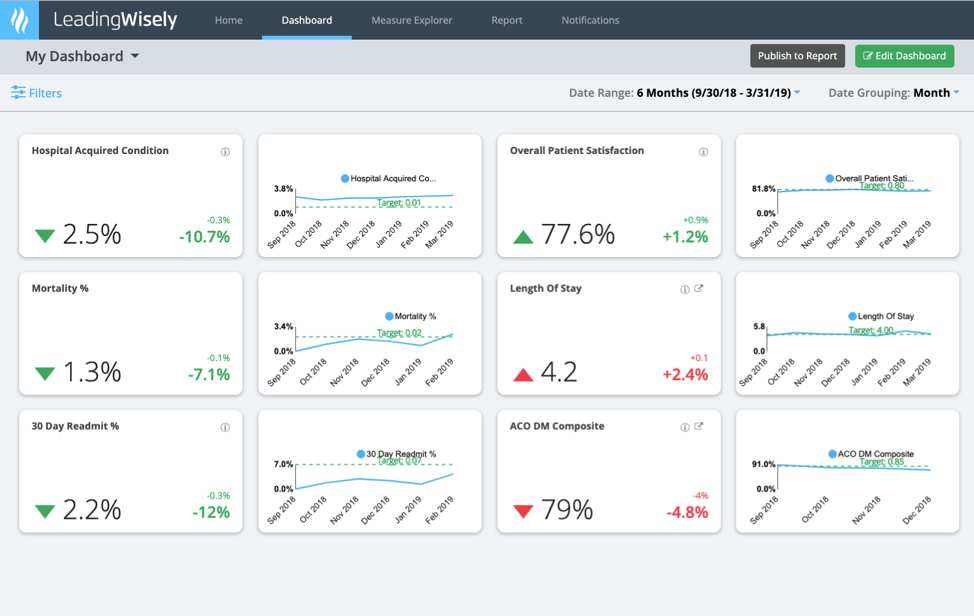

Figure 2 shows a dashboard suitable for board-level reporting, as well as for the executives who will need to speak to performance:

Providing information to a board of trustees or a board committee requires a different measurement and presentation strategy than what a service line or department needs to support its operations and performance improvement projects. The most valuable board resource is their time. The trustees consist of a mix of volunteer community members, often with no clinical experience, as well as clinicians from the community. The trustees typically conduct their deliberations with the CEO in attendance as well as other health system leadership. Leadership must present healthcare information clearly so that the board understands performance against meaningful targets but also in a way that empowers the board to raise tough questions about opportunities for improvement. Beyond the staff providing honest and meaningful information, while continuously disclosing failures, a strong board most have sufficient subject matter expertise and independence to hold providers accountable. Presented data must demonstrate that the hospital or health system is placing the safety of the patient first and is looking at the right measures of care. Targets and benchmarks must be clear enough to trustees to encourage them challenge each hospital or health system to improve care and eliminate all patient harm.

Despite the launch of a quality and patient safety movement in the early 21st century, too many hospitals and health systems still lack the resources to give their boards the information required to meet their fiduciary responsibilities. To support safety and quality progress, the industry must accelerate its ability to collect data from an ever-increasing quantity of sources, as well as transform that data into meaningful information for the board of trustees to digest.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest: