When expenses exceed revenue, business has a financial problem. In healthcare, the focus has been on revenue for so long, we’ve lost sight of runaway costs brought about by high labor and technology expenses, inefficient use of resources, and supply waste. Recognizing the cost problem is a big first step toward solving it.

Five expense-controlling strategies can play a significant role in returning healthcare systems to a stronger financial position:

1. Refocus on labor management.

2. Manage employed physicians.

3.Change the patient encounter environment.

4. Augment standard approaches with technology.

5. Manage patient access and flow through the healthcare system.

With new, value-based payment structures, shrinking margins, and decreasing reimbursements, this insight offers some new ways to think about expense inefficiency and how to get costs under control.

Download

Download

For too long, U.S. hospitals have focused on increasing revenue, volume, and growth. At the same time, the healthcare system has wasted hundreds of billions of dollars on supply chain inefficiencies, variation, service duplication, and suboptimal labor management. Unfortunately, the healthcare cost problem has put the industry in a financial quandary.

Recently, Moody’s Investors Service reported that hospital median operating margins fell to just 2.7 percent in fiscal year 2016, and operating expenses grew faster (7.5 percent) than operating revenues (6.6 percent). To address these margin challenges, healthcare systems need to change their business models to include a focus on costs.

While systems can deploy multiple strategies to impact revenue and volume, traditional methods are antithetical to value-based care. Hospitals can raise prices, but Medicare holds reimbursement increases steady at only one or two percent a year. Commercial payers—where hospitals have traditionally profited—provide increases, but those are increasingly tied to quality measures that put hospitals at greater risk. This risk-based payment structure is expanding with the growth of alternative payment models.

The revenue side of the earnings equation has changed, so hospitals need to change the cost side as well. Over the past 20 years, consumer prices for inpatient services increased 195 percent, prices for outpatient healthcare services increased 200 percent, and prices for all medical services jumped 100 percent. Furthermore, consumer prices for prescription drugs doubled, and prices for nursing homes and adult day services more than doubled during this time. In comparison, consumer prices for all items increased just 50 percent over this same period.

With high-deductible plans, consumers are bearing more and more of the healthcare cost burden. Healthcare systems need to identify the root causes of high costs and implement smart, creative solutions to improve their financial health and prosper under value-based care.

Let’s explore what’s behind healthcare’s cost problem and some ways to get it under control.

Healthcare providers (hospitals and clinics) may have diminished control over revenues, but they can control hospital operating expenses, which comprise all the costs of taking care of patients: labor, supplies, utilities, equipment, buildings, property, and capital. A few of these expense categories are driving the current cost problems:

According to the Harvard Business Review, the main cause of operating expenses outpacing revenue growth has been the size of the healthcare workforce, which accounts for almost half of all healthcare expenses. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects impressive healthcare labor growth:

In 2000, national health expenditures were roughly $1.37 trillion. In 2015, this number had risen to more than $3.2 trillion; labor is a big chunk of this expense. If salaries increase between two and five percent every year, but reimbursement increases by less, the expense and revenue lines will cross soon. Even though everyone expects annual raises, without change to the overall expense structure, this isn’t sustainable. Healthcare systems must figure out how to work smarter rather than harder, and how to be more productive.

The healthcare industry has lost its focus on costs partly because it has pushed hard on the patient experience, access to care, and quality issues; however, hospitals need to be more efficient and productive with their resources. For example, to be more service oriented, hospitals have adjusted the hours of operation for outpatient services, offering flexibility by opening the doors for early morning, evening, and weekend hours to accommodate working people. But then volumes become diluted in the middle of the day. Extended hours are challenging from a financial perspective, even though patient satisfaction scores may be high. Healthcare leaders need to redesign their systems to be more effective in terms of productivity and service. It’s a balancing act to synchronize quality, satisfaction, access, and cost components.

More than half a million experienced nurses are expected to retire by 2022, and 1.1 million new RNs will have to replace the retirees and fulfill the healthcare needs of a swelling patient population. Physicians and many other clinical disciplines are in this same predicament, though less severely.

Healthcare systems will fight to become the employer of choice. If hospitals can’t expand available resources, they must get them from somewhere else (e.g., contract labor), which will double, triple, or quadruple the cost of labor and ultimately impact prices. Suddenly, the labor expense line will be unmanageable, even with fewer people on staff.

Hospitals employed 38 percent of all U.S. physicians in 2015, a 50 percent increase from 2012. From a strategic perspective, there are many good reasons for employing physicians; doing so captures the revenue stream of their patients and facilitates population health activities. Employing physicians increases the payroll, but it also has benefits, so healthcare systems need to diligently monitor both.

Ten to 15 years ago, not-for-profit health systems focused on productivity, but along came new enterprise systems and EMRs, which distorted this focus. Healthcare systems were promised many things that didn’t happen with EMR conversions. Often, the technology was installed without sufficient integration because the process was usually rushed. Clinician workflows and methods weren’t studied and optimized, which resulted in workarounds to accommodate the technology. Healthcare did not realize the efficiency gains typically seen in other industries by installing technology and, in some respects, the technology has cost more money than it has saved.

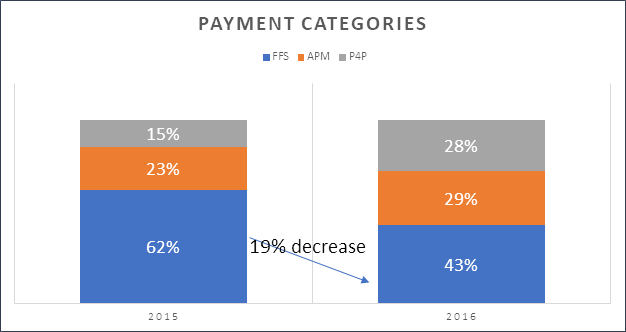

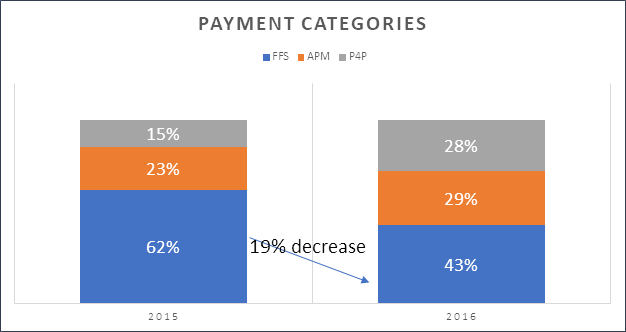

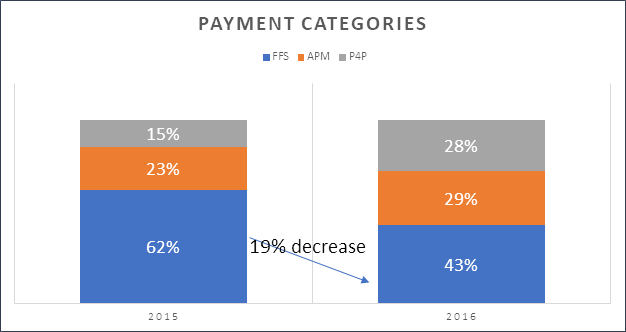

The risk and reimbursement structure in healthcare adds to the cost burden. The American Hospital Association reports that health plans and systems are slow to pursue capitated payment plans. As shown in Figure 1, only 29 percent of medical payments were linked to alternative payment models (APMs) in 2016 (e.g., shared savings, shared risk, bundled payments, or population-based payments). Payers often reimburse on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis (43 percent of healthcare dollars in 2016), but put providers at risk for various measures, setting up a greater risk component than has ever existed. For example, payers compare competing hospitals on utilization and reward the better performers; It is in their interest to reduce utilization, thereby reducing claims.

Medicare reimbursements generally fall short of actual costs, so health systems and providers struggle to better match their costs with reimbursement. Medicare has never increased its reimbursement rates to match inflation. Medicare also applies restrictions to many clinical processes. For example, when a patient transfers between services, it must be under the same DRG. Or before patients can transfer to a skilled nursing facility, they must have been in the hospital for at least three days.

Medicare, in general, reimburses less than commercial payers do. One long-time mantra states that hospitals should operate at a cost structure that allows them to be at least breakeven at a Medicare reimbursement rate. And even though commercial rates are rising, they aren’t doing so as quickly. In some respects, the goal for commercial payers is to lower their reimbursement rates to match Medicare’s. They may never quite get there, but every time Medicare makes a significant change in how they’ll reimburse, the commercial world eventually follows suit.

Finally, there are many reasons why healthcare systems need to be concerned about inefficient patient flow through their hospitals. Poorly managed flow leads to higher volume and overutilization of emergency rooms and intensive care units. It creates surgery delays and longer length of stay, the latter which increases infection rates. Healthcare systems need to do a better job of optimizing operating room schedules, filling exam rooms, and generally streamlining physical asset use and managing capacity.

While the cost problems appear to be out of control and worsening, healthcare systems can minimize them through creative new approaches to how they conduct their operational, clinical, and financial business.

Hospitals can get more productive by refocusing on labor, a focus that was lost in the past few years for many reasons. Hospitals need to better match resource demand, making sure they have the right staff with the right skill for the workload.

Many hospital systems acquire physician practices and then remain hands off in their day-to-day operations, but it’s important to align physician incentives with the rest of the system. Physicians are accustomed to benchmarking through the Medical Group Management Association, so equivalent internal review is appropriate, which means digging into their operations and inquiring about things like how much support staff is needed. Now that the practice is part of the system, what services are duplicated, what needs to be systematized, and what needs to stay at the practice? For example, physician practices may not be accustomed to collecting revenue based on the policies of a larger healthcare system, so these types of processes need to be standardized. Managing employed physicians applies a new level of discipline where it hasn’t been applied before.

To adapt to changing risk and reimbursement models, healthcare systems need to evolve how they oversee certain patient types. For example, telemedicine is one way to use technology to modify resources, allow centralization, and apply specialized skills. And regulations are changing to accommodate greater reimbursement for telemedicine.

In 2015, Kaiser Permanente processed 59 million patients through its online portals, virtual visits, or the health system’s apps. That was the first year virtual encounters outpaced in-person encounters. Telemedicine, along with email and other connectivity with clinicians, can take healthcare to a whole new level, reducing the need for office visits. Clinicians can still treat and deal with patients in an appropriate way using technology (e.g., doing exams over video), which changes the workflow of how a patient accesses the system and receives service.

The healthcare Internet of Things is also changing the patient encounter environment. This market is projected to reach $117 billion by 2020 with more than 25 billion connected devices. Wearable monitors, smartphone diagnostic applications, and remote scanning and imaging devices, to name a few, represent new technology that holds potential for reducing operational and clinical costs.

Many healthcare systems don’t truly understand the costs of the care they provide. Minimizing variation and standardizing clinical care delivery positively impacts costs. Tools like the CORUS® cost management suite, can be used to understand the true cost of providing care across the continuum and can relate those costs to patient outcomes. CORUS gives providers the ability to see clinical activity data at a very granular level.

While standardization is critical to managing costs, clinicians may not react favorably to the notion of a cookbook approach, even though most of them already practice consistency and standardization when they treat patients. Clinicians follow specific steps during every exam, process patient variables, develop diagnoses, and recommend treatments. Clinicians conduct many standard processes for each patient, with appropriate deviation when necessary.

Clinicians tend to be driven by data and competition. Show them data that compares their performance to their peers with quality outcomes, and they will do everything in their power to end up at the top of the list. This is a classic tactic for getting this very important stakeholder group motivated toward understanding and controlling costs for improving outcomes.

Healthcare systems can also do more to improve the bottom line by better managing their revenue cycle. Systems must improve what is commonly referred to as revenue integrity: their ability to appropriately document a medical bill, justify it, and collect it. This boils down to how well the system adheres to clinical documentation improvement (CDI), following the premise that if services are not well documented, then they weren’t rendered and cannot be appropriately reimbursed. As the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) says, “Successful clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs facilitate the accurate representation of a patient’s clinical status that translates into coded data. Coded data is then translated into quality reporting, clinician report cards, reimbursement, public health data, and disease tracking and trending.”

Historically, wherever patients have accessed healthcare—in the ER, the ambulatory setting, or the inpatient setting—is where they have received treatment. Over the past few years, however, this has been better controlled by case management workers who focus on patient navigation and reducing length of stay. Improved control puts healthcare systems on the right path to managing demand.

Healthcare systems must take a business approach to examining capacity, controlling where patients should be and what services they should be receiving. This control also depends on the disease state of the patient. If someone presents with cardiac issues, the protocols are well understood almost all the time. If patients aren’t where they should be, then case managers can place them in the right environment (e.g., specialist’s office or urgent care) where they aren’t using resources needed for emergency situations.

There is variation in the pathways patients follow through a hospital, but there is an expected or typical approach and use of services that each patient needs. Some deviation from the expected is legitimate; for example, the patient presented with comorbidities that needed to be addressed. But sometimes, deviation exists just because something has always been done a certain way. Providers need to use their tools and technology for treating patients of certain disease types in more standardized ways, and then deviate when a patient requires it. Then providers can manage resources more from a capacity perspective rather than just trying to fill beds, and better influence what resources are being consumed in the delivery of care.

Healthcare systems previously relied on payment increases to meet bottom-line needs, particularly from commercial payers, but now the expense trend is growing faster than the payment trend. The United States already spends more on healthcare per person than any other country, and increasing costs are only putting U.S. healthcare consumers at greater risk.

Healthcare has a cost problem, but the solutions exist. Healthcare systems need to recognize the problem, identify the problem’s sources, and then begin the improvement journey. Systems must pay close attention to the increasing costs of labor, labor shortages, acquiring physician practices, technology implementations, and increasing risks accompanied by decreasing reimbursements. But recognition is only half the battle. Adopting the appropriate technology, embedding the required expertise, recruiting targeted human resources, and spreading best practices all combine to win the cost war.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.