Thibodaux Regional Medical Center recently aimed to enhance its inpatient admission process. The organization leveraged Health Catalyst methodologies and Lean Six Sigma processes to analyze delays and wait times and identify inefficiencies like redundant data collection. These initiatives have significantly improved admission wait times and ensured a better overall patient experience.

Admitting a patient to inpatient care is a complex process that, unless carefully managed, can lead to long delays in service and a poor patient experience. Waiting for admission paperwork, or for a bed to be assigned can be frustrating for anyone. But for patients who are sick, or for an exhausted mother with a crying baby who needs to be admitted, wait times can become emotionally and physically difficult as well.

Thibodaux Regional Medical Center’s consistent focus on patient satisfaction has earned the 185-bed community hospital, located one hour southwest of New Orleans, the Healthgrades® Outstanding Patient Experience Award™ every year since 1998. Not surprisingly, when Thibodaux leadership recently analyzed the hospital’s inpatient admit process, they did so from their patients’ point of view and were determined to cut admission wait times. Using focused process improvement methodologies, areas of waste were uncovered, exposing problems such as redundant data collection, and inconsistent processes, which would require innovative solutions.

Integrating concepts from the Health Catalyst improvement methodology into its own Lean Six Sigma processes, and with the support of professional services from Health Catalyst, Thibodaux deployed a systematic set of solutions to significantly improve the admission process.

Thibodaux’s efforts are driving measurable improvements in the hospital’s inpatient admission process.

Each year, American hospitals conduct 35.4 million admissions, according to the American Hospital Association. Of those, 16 million occur through the emergency department (ED), suggesting that more than 19 million are direct admits.1 A direct admit may be either planned or unplanned. Planned direct admits happen, for example, when a patient is scheduled for a routine procedure. Unplanned direct admits can happen when a sick patient presents at a physician’s office, for instance, and the physician decides to admit them directly to the hospital rather than send them through the ED.

Direct admission has the advantage of driving improved patient flow, shorter ED wait times, a better patient experience, and improved quality and continuity of care.2 However, admitting a patient to inpatient care, whether planned or unplanned, is a complex process that requires careful coordination among physicians, nurses, registration staff, and others within the organization. Ineffective admission processes can lead to long wait times for patients, staff frustration, and a negative patient experience, as well as communication and handoff problems that can impact patient safety and quality.

Long wait times, in particular, are associated with decreased patient satisfaction. This is true whether a patient is waiting in their doctor’s office, in the ED, or to be admitted to a hospital. In fact, the difference between a five-minute wait and a 30-minute wait is a significant 15 percent drop in patient satisfaction.3 The tight correlation between wait time and patient satisfaction is important not only to maintaining customer loyalty but also because patient satisfaction scores have been used in determining hospital reimbursement from CMS since 2012.

Long before then, Thibodaux had developed an innovative approach to providing patient services via a “Medical Mall.” Its Medical Mall offers a number of outpatient services such as same-day surgery, a Center for Digestive Disorders, a Heart & Vascular Center, and a Cardiac Rehabilitation Facility.

Many of Thibodaux’s over 1,000 annual direct admits come from its physician offices. When the hospital’s leadership recognized that inefficient and redundant processes were leading to unacceptably long delays for patients being admitted to the hospital from their Medical Mall, they set out to address the problem.

Thibodaux’s first step in improving the inpatient admit process was to assess their current admission practices and identify gaps or areas for refinement. The project was the result of a request that came directly from the hospital’s Chief Executive Officer, Greg Stock, and his vision to improve ease of use for all involved in the admit process. Mr. Stock challenged the process improvement team to analyze the admit process with a focus on improving ease of use for staff, decreasing wait times for patients and creating an easier process for physicians to admit patients into the hospital.

After carefully reviewing the process with frontline staff, Thibodaux identified three primary areas of concern, similar to those found in hospitals nationwide: 1) the process was cumbersome and mostly manual; 2) there were several breakdowns in communication along the admission pathway; and 3) the process was not patient-centric.

While Thibodaux had invested millions in its EHR and other information technologies designed to improve patient care, the hospital’s inpatient admission process was still entirely manual, involving documentation on paper and faxing. This led to errors such as lost faxes, and to cumbersome processes such as multiple phone calls to track down information while patients waited. The manual process also led to inefficient handoffs, redundant data collection, as well as delays in getting necessary information, doctor’s orders, and bed assignments so care could be initiated.

Another problem they observed was that patients often showed up at the admit desk without physician orders, or without advance notice. They would then have to wait while the admit coordinator tracked down the information needed to admit them and assign a bed so care could begin. Even when orders were received before the patient’s arrival, they seldom contained all of the necessary information. As a result, staff wasted time making follow-up phone calls, and in re-work. Moreover, the admitting phone call was typically made by a non-clinical person at the physician’s office who was unable to provide the information needed to determine the patient’s acuity, and where best to place them.

In addition to problems with communication and efficiency, Thibodaux’s inpatient admission process generally was not designed with the patient at the center. Rather than moving swiftly through the admit process to receive care, patients had to wait for orders to arrive, for a room to be assigned, or for paperwork to be filled out. In addition to waiting, family members sometimes had to leave their loved one at a time of need to complete necessary paperwork. Patients and family members had to spend prolonged time in a public waiting area when they were unwell, tired, or anxious.

Once Thibodaux’s leaders had identified the issues with the hospital’s existing inpatient admit process, they established an interdisciplinary core team tasked with improving admission times. The team consisted of members from case management, customer service, organizational engagement, patient care services and nursing. Integrating concepts from the Health Catalyst improvement methodology into their own Lean Six Sigma processes, and using the support of professional services from Health Catalyst, Thibodaux’s core team leveraged a data-informed prioritization process to identify their project, baseline, and aims.

The team started by mapping out their current admit process and analyzing problem areas using fishbone diagrams to drill down into root causes and possible solutions. The team knew that it was critical to ensure the right people in the right roles were engaged in creating solutions, therefore throughout the improvement process, the team called in additional team members with special expertise, such as admissions, information technology, and engineering.

The team’s original aim statement set a target of reducing admission time by 20 percent. But they soon decided to further challenge themselves by adopting a more aggressive stretch goal—one that they felt would be impactful enough to be recognized by the patients and families, and that would improve patient experience in a demonstrable way. They eventually settled on the ambitious aim of reducing inpatient admission time for direct admits by 30 percent and improving the corresponding balance metric of patient experience to the 99th percentile.

Thibodaux’s executive leadership had spent years nurturing a culture of continuous improvement and patient-centered care. That organizational mandate gave the core team the support they needed to implement solutions to the admissions process in three key areas:

The team’s first priority was to explore viable alternatives to paper forms and faxes. Partnering with their IT colleagues, they were pleased to learn that their current computer system would support the development of online processes. Working with Thibodaux’s IT analysts, the team developed an online “short form” registration process, which contains all of the information required to preregister a patient, assign a bed, and alert others that a patient will be admitted. Eliminating the use of faxes also removed a lot of stress and inconvenience for the staff who no longer had to wonder whether a fax made it to its destination or whether the right fax had been received.

Taking automation one step further, the team also implemented an online bed board to alert others when a patient will be admitted. Today, when a patient arrives at the admit desk, they are expected, and the admit clerks pull up the needed information on their computer, eliminating unnecessary waiting and phone calls. After eliminating the manual process, Thibodaux immediately experienced an improvement in efficiency and wait time.

The next step was to improve the quality of the information coming from the admitting physicians’ offices. To that end, the admit coordinator reached out to physician clinic managers, and reeducated them regarding appropriate completion of forms and which patient-specific information they must share when calling to admit a patient. The admit coordinator also shared a checklist of key information needed to admit a patient that could be posted near the nurse’s desk. This information helps to determine if the patient meets the criteria for admission, what their acuity is to make sure they get admitted to the right unit, and whether they have special needs, such as making oxygen available when they arrive.

As soon as the clinic staff understood what happened to their patients when they arrived at the hospital, and how long they would have to wait if they did not have the right information, the staff were motivated to help. This collaboration improved the quality of the data received from the clinics, speeding the admit process by eliminating unnecessary phone calls to track down missing information, and gave the patient confidence that the inpatient unit was expecting them.

Once the team had resolved the key issues slowing the admission process prior to the patient’s arrival, they focused on improving the registration process post-arrival. The old registration process required the patient to sit at an admit desk located in the public lobby while the registration was completed. The team wanted to do away with this process and complete registration at the point of care, speeding the patient to the floor as quickly as possible. Additionally, studies have shown that switching to bedside registration improves patient satisfaction.4

With mobile, or “bedside” registration, the admit clerk accompanies the patient to their room and completes the registration process there. This eliminates a source of waiting, gets the patient and family comfortably out of the public area, and enables care to be initiated as soon as the patient arrives.

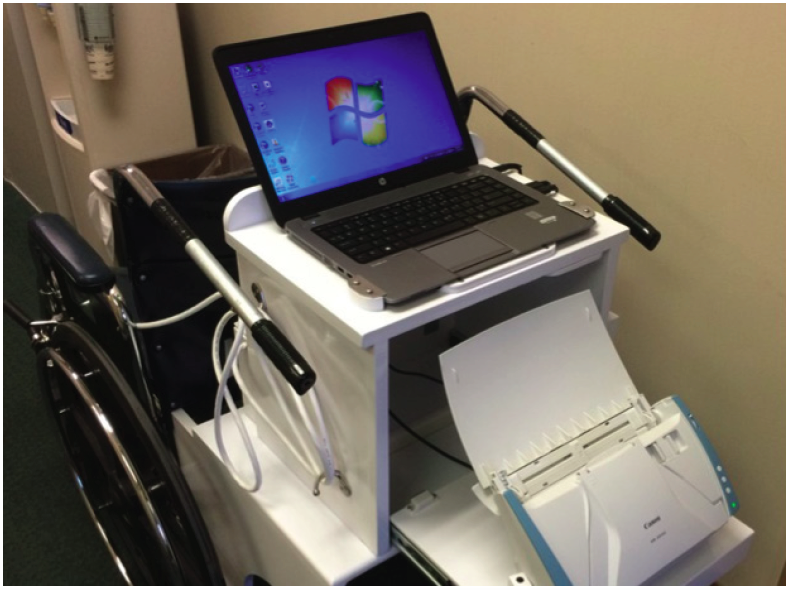

To switch to mobile registration, Thibodaux needed a way to transport the patient to the room while carrying a computer and scanner. They reached out to their engineering department and presented them with the problem. Ultimately, Danny Hebert, a member of the hospital’s maintenance crew, eagerly accepted the challenge. Hebert built an innovative mobile registration cart (see Figure 1) that was attached to the back of a wheel chair, yet still light enough for a registration clerk to push wherever the patient needed to go, included a back-up battery system, and a removable top that enabled clerks to place the laptop on a bedside table or counter in order to face the patient bed while they filled out the registration information.

Thanks to the mobile cart, and the ability of the registration process to follow the patient, families no longer had to leave their loved one’s side to finish paperwork. Patients no longer had to wait in a public waiting area while ill. This relieved stress and frustration for both the registration staff and the patient.

The success of the new process was demonstrated recently when a patient arrived at the hospital by ambulance to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The patient had been pre-registered prior to arrival, and was assigned to a bed. When the patient came through the door, the ICU nurse was waiting for her, and she was immediately transported to her room. Registration staff were in the ICU waiting with the mobile registration cart, and worked with the family to complete the registration while the nurse worked on admitting and treating the patient.

Many patients have commented positively on the new mobile registration process. The registration staff unanimously supports the new process, convinced that they are contributing significantly to an improved patient and family experience.

Thibodaux’s commitment to patients, use of proven process improvement methodology, innovative solutions, and collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork paid off in an impressive reduction in admission times, surpassing the team’s stretch goal of 30 percent:

By redesigning its inpatient admit process, Thibodaux has improved patient and family experience, reduced staff stress and frustration, and improved communication and handoffs at every stage of the process.

“The registration aspect of a patient admission has always been viewed as tedious and repetitive, in most instances. Our clerks are excited about our innovative new process and patients have been quite satisfied, as well. We feel that giving a patient our full attention by greeting them at the door and bringing them to their room for immediate care has enforced our team effort to put our patients first!”

– Sheri Sothern, Patient Access Manager

Thibodaux plans to sustain the gains made through its new inpatient admit process with ongoing education and collaboration with community providers. The hospital also plans to expand its improved process to patient admissions from the ED. In the long term, Thibodaux is working towards a fully electronic admission and registration process to provide patients with an even faster and more efficient registration experience.